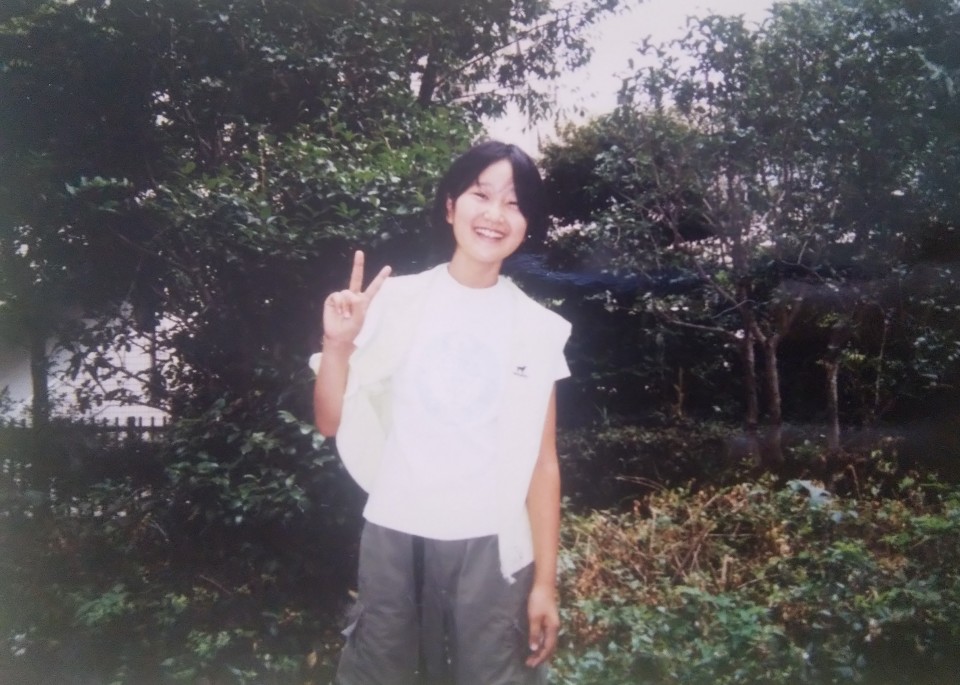

Yukiko Okimura was just 11 years old when her mother, a single parent, was left paralyzed by a traffic accident on her way to work in Kanagawa Prefecture, west of Tokyo, in 2001.

A tragic upheaval already in the life of any elementary school kid, what made it doubly transformative for Okimura was suddenly finding herself taking on the role of her mother's main carer, with no relatives ready to step in.

Nevertheless, Okimura was far from alone in being saddled with what is usually regarded as an adult task. A recent government survey has revealed that there are, on average, one or two such "young carers" routinely looking after family members in the classrooms of Japan's junior and senior high schools.

In April, releasing the results of its first-ever survey into the phenomenon, Japan's education and welfare ministries said 5.7 percent and 4.1 percent of junior and senior high school students, respectively, take care of family members, including younger siblings, the disabled, and elderly.

The survey conducted between December and January defined young carers as children who routinely do household chores and look after family members, taking on tasks that are seen as compromising their rights as children and ability to lead normal childhoods.

Welfare experts attribute the rise in Japan of the phenomenon, first noted in Britain in the 1980s, to an increase in nuclear, double-income, and single-parent families.

In the case of Okimura, since her mother lost her job and could not seek support from relatives, she found herself not only physically caring for her mother but also looking to make household economies and responding to legal procedures related to the traffic accident -- all on top of her own school studies.

Meanwhile, given the public's strong expectation that adults and not children should be caregivers, many young carers conceal their situation, according to Okimura, although she herself did not.

Now 31, she said she felt a perception gap open up between her and her friends as Japanese parents tend to do everything for their children.

"This situation makes young carers believe their friends won't understand them, even if they voice their worries over caring. That was true for me," she said.

According to the survey, more than 80 percent of junior and senior high school students said they had never heard of the phrase "young carer," indicating how little discussed the issue has been.

Meanwhile, 67.7 percent of junior high school students and 64.2 percent of senior high school students said they never consult with anybody about their worries, suggesting an overall tendency to keep things in that may exacerbate the isolation felt by kids looking after relatives.

Okimura recalled her junior high school days were the most difficult time of her life. Her mother's home caregivers made regular visits, but they were supposed not to do household chores, like cooking and washing clothes, except for the direct recipient, meaning her own needs were not met.

As a result, she had to do all the leftover tasks by herself and had little time to study. So worried were her homeroom teachers that they sometimes came to visit her and offer a sympathetic ear.

After Okimura and her mother moved to a neighboring city to enter high school, her mother was able to receive longer-term public support. That reduced her care burden and enabled her to study more and work part-time.

After she succeeded in enrolling in university with the help of scholarships, her mother urged her to live alone and devote her time to herself. She managed to do so by earning enough through jobs to cover her living costs and school expenses.

She now runs a company sending caregivers to the disabled out of gratitude toward her teachers, social welfare systems, and her mother's support for her. "I believe it is necessary to promote social welfare that doesn't rely on nursing care by family members in Japan," she said.

The poll also found nearly half of young carers look after their family members almost every day. While the average number of hours they spend on caring per day stood at 4.0 hours for junior high school students and 3.8 hours for senior high school students, more than 10 percent in both categories spend over 7 hours.

Tomoko Shibuya, a sociology professor at Seikei University in Tokyo, said that in families where both parents hold demanding jobs with long hours, they can sometimes leave their children to look after siblings.

"I think that is very tough for them (the kids) and is one of the typical factors for young carers in Japan," said Shibuya, an expert on the issue.

"The issue has not been closely analyzed in Japan, where awareness of children's rights has remained low and people believe it is a good thing for children to work hard for their family members and help each other," the professor said.

Shibuya said the first national survey was significant because it shed light on the young carers issue in a society that has tended to view children helping out as a family matter best dealt with within families.

She said minors end up becoming caregivers because of the way the welfare system limits care support to those directly in need -- in Okimura's case, her mother alone, with her own needs ignored -- and that change was needed.

"It is necessary for society, schools and family members to closely look at what kind of care children are shouldering and whether that is too heavy for them as well as try to grasp the actual situation by quantifying the amount of care they provide," Shibuya said.

"Without systems that take into consideration such a situation, nobody will be able to give birth to children and raise them," the professor warned.

After releasing the survey and hearing opinions from people with firsthand experience, the government is planning to compile a rescue package for young carers, including expanding consultation services, in May.

By Satoshi Iizuka,

By Satoshi Iizuka,