Every few weeks, over many years, I used to spot a slight and silver-haired gentleman, quiet but polite in demeanor, walk briskly through Union Station in Washington on his way to an Amtrak train.

The conductors all seemed to know him, and subtly nodded, even though they rarely exchanged words as he glided by. A few times I happened to spot him from afar riding in the same train car as I -- always economy. Usually alone, working from a battered beige briefcase at the end of the car, as he read, marked up, and carefully filed papers back within it.

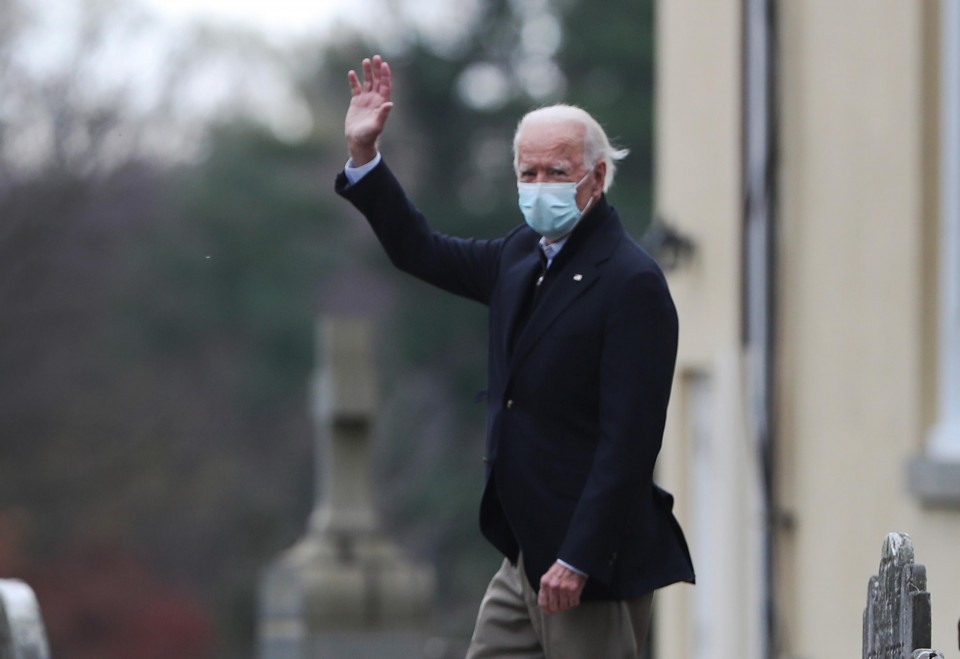

The modest, silver-haired gentleman was Joe Biden -- now president-elect of the United States. He was headed home to Wilmington, Delaware -- chairman of the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee, but headed home to his family, and to the community where he had lived, and represented in Congress, for four decades. Headed home every day, 110 miles each way, four hours round trip, for the largest part of his adult life.

The emotional pull of home for Joe Biden was, and is, clearly a powerful one. I wondered then, and I wondered again in recent days, as Biden prepares to assume our presidency, both why home is so powerful for him, and how home had molded him over the years.

Unlike Japan, American society is generally a fluid one, with few emotional parallels to the power of "furusato." Yet for Biden, "home" clearly has a special attraction and power that is unusual for Americans, although Japanese can perhaps better empathize.

No doubt a major part of Biden's attachment to home, and to his roots, is because life for him has seemed so fragile. His father, once affluent, struggled for employment amidst the economic stagnation of his hometown in the coal-mining northeast corner of Pennsylvania after the Korean War, forcing the family to move to a rented apartment in Delaware.

His wife Neila and baby daughter Naomi, only one year old, were suddenly killed by a heavy truck only six weeks after Biden's election to the Senate, and he was sworn into the Senate virtually at the bedside of his two badly injured yet surviving sons.

Biden, as a widower, felt impelled to commute home to care for them. The eldest of the two, Biden's son Beau, rose to be attorney general of his home state, Delaware, and seemed a promising successor to his distinguished father, only to be struck down by brain cancer at an early age.

For Joe Biden, one part of "home" is clearly his religion. Biden is a Catholic, only the second in American history, and a devout believer who regularly attends religious services, and carries a rosary with him every day.

Yet home also for him has an important territorial dimension. Where Biden has lived, and what he has learned existentially from those surroundings, are a central element of who he is today, powerfully shaping Biden's future course as president of the United States, even as he reaches out to the broader world.

Joe Biden lived in three rather different cities -- all of them small -- across his formative years. He was born in Scranton, Pennsylvania, an anthracite coal-mining town in the northeast of the state, with a history of labor militancy, whose population today is little more than half of the 140,000 that it was in the 1930s.

The Bidens lived in a modest single-family home on Washington Avenue there, even as his father handled a variety of jobs ranging from furnace cleaner to used-car salesman, until he was almost eleven years old.

Neighbors mentioned, when I visited earlier this year, that Biden came back frequently, even as senator and vice president, and he did indeed drop by on Election Day, 2020, inscribing "From this house to the White House" on the wall of his boyhood bedroom.

Scranton is striking even today for its proliferation of Ukrainian Catholic, Greek Orthodox, and other ethnic churches, as well as monuments to ethnic European comrades of George Washington and other American revolutionary heroes around the town square. Scranton has clear working-class European immigrant roots, although Donald Trump nearly carried it in the recent presidential election.

Joe Biden spent his junior high and high-school years in Claymont, Delaware, where his father and the family moved in search of work in 1953. Claymont, a town of less than 9000 close by the Delaware River, is like Scranton both working class and highly diverse.

Even today its population is 20 percent ethnically Irish, as Biden himself is, but also 7 percent who still speak Polish, and 28 percent African American. Employment is concentrated in the services, with 16 percent in retail, as Biden's father was. Claymont's median income, like Scranton's, is below the national average.

Biden attended the nearby University of Delaware, where his international consciousness began, in opposition to the budding Vietnam War. After graduating from college, receiving a law degree at Syracuse University, and getting married, Biden moved to the suburbs of Wilmington, Delaware -- first to Newark, and then to Greenville, where he has lived for most of the past 45 years, even amidst a 47-year career in Washington.

In both cases, Biden bought into neighborhoods with historical ties to the wealthy Dupont family, founders of Dupont Chemical, traditionally the one Fortune 500 company located in Delaware. At last, the Biden family became entwined with America's middle and upper class.

Biden's first two hometowns, in Scranton and Claymont, were emphatically working class. Scranton was also industrial. The Wilmington suburbs are sharply different from both.

Wilmington itself, as capital of the state with America's most protective corporate legal provisions, is the home of America's credit-card industry, and also home to Dupont, a major chemical multinational. Unlike Biden's earlier two home towns, it is deeply entwined with the nation's establishment, and the world beyond our shores.

So are the past two decades of Biden's career, in the leadership of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and as vice president. Yet as Joe Biden assumes the presidency of the United States, he cannot avoid remembering Scranton, or Claymont, or the human struggles across his life that have linked him so emotionally to memories of home and the people who he sees as still suffering there.

(Kent E. Calder is vice dean for Faculty Affairs and International Research Cooperation at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies in Washington and director of the Reischauer Center for East Asian Studies at SAIS.)

By Kent E. Calder,

By Kent E. Calder,