Fumikazu Matsuzaki saw his business take a one-two punch from the coronavirus pandemic.

His 40-year career in the "hanko" seal game was put suddenly in peril when the traditional document formalization procedure became the target of criticism for its inherent inefficiencies, particularly as more people were forced to work remotely.

Many in Japan called for the long-held practice of authorizing and formalizing documents via red stamped seals to be abolished.

Then Matsuzaki lost his international revenue stream when sales of his tailor-made hanko for foreigners dried up due to a slump in visitors and tourists who normally ordered them as unique and personalized souvenirs or gifts.

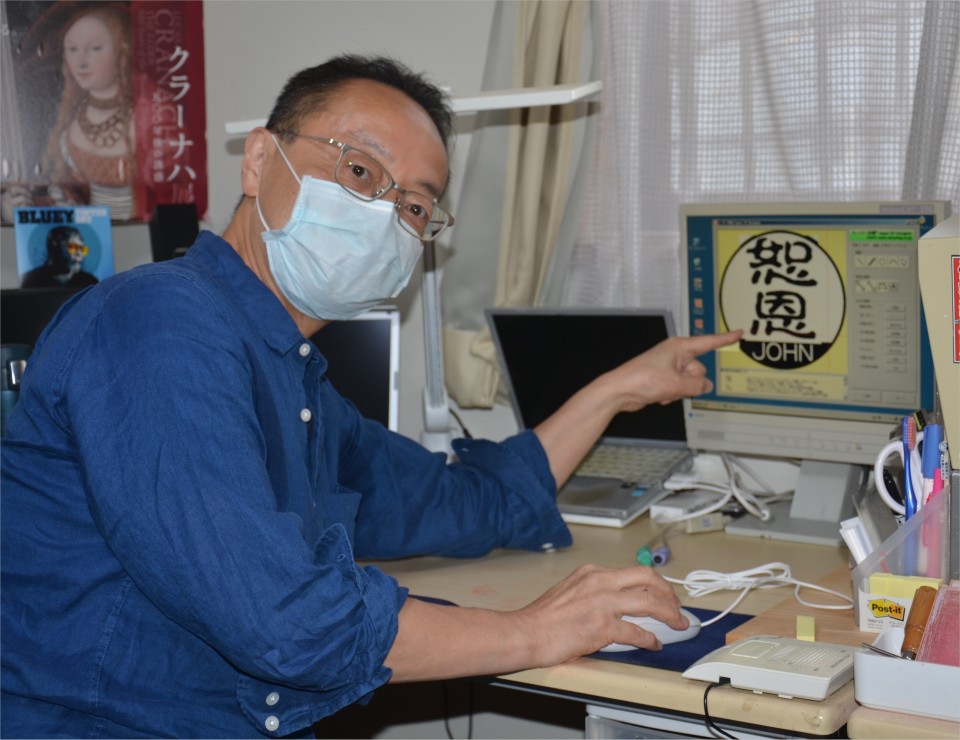

Forced to search for new business with his customers now stuck at home, Matsuzaki latched onto a novel idea: making digital hanko.

"I was down in the dumps because you see something that you've done for 40 years suddenly labeled as 'not needed anymore,'" said Matsuzaki, a third-generation hanko shop owner in Tokyo.

"But it's also true that I got out of that negativity and took a different look at life because of the hanko."

The spread of the novel coronavirus in Japan has prompted the government to call for more people to work from home to reduce the risk of infection.

With an increasing number of companies acquiescing, hanko were thrust into the spotlight when complaints began surfacing from people forced to physically go to their office simply to make their mark on a contract or other document.

Matsuzaki says the deep-rooted hanko tradition, or the existence of seals at all, should not be solely blamed for Japan's seemingly backward reliance on paper and ink. That said, he acknowledges the time is likely ripe for reassessment.

"I don't deny there may be cases in which hanko are not necessary. What needs to be done is to rethink what is necessary and what is not in Japan's hanko-dependent system," said the 61-year-old.

In the government's view, the absence of hanko marks does not invalidate a contract unless specifically mentioned. It has joined forces with business groups, including the powerful Japan Business Federation, to move toward a system in which digital documents can be considered official.

Kotaro Nagasaki, governor of Yamanashi Prefecture in central Japan, an area known for its hanko seal makers, was quick to express displeasure with the sudden shift.

"Despite calls for electronic verification, I believe seals should be respected as showing the identity of an organization or a person or as a symbol of trust," the governor told a prefectural assembly session in June.

Japanese use hanko seals to authenticate contracts and other important documents, a practice that some critics say has kept companies drowning in a sea of paper.

Established in 1921, Matsuzaki's shop Bunbukudo Inbo Co. is both a mixture of old and new. It sells handmade hanko made by craftsmen who spend weeks carefully carving the delicate pieces. Japanese people often register such seals with authorities as a way of identification and use them on important occasions such as buying a house or car.

But not all hanko are created equal, and not all are laboriously carved by a person. Other, cheaper, more everyday hanko can be produced by machine in around half an hour at Matsuzaki's store.

Despite the groundswell for change, Matsuzaki says the pandemic has not caused a sudden change in demand for hanko at his store, apart from the drop off in customers from abroad.

Japan was temporarily put under a nationwide state of emergency in April and May, with the government requesting that people refrain from nonessential outings.

"I was worried (about the future) around April because hanko seals were being treated as something bad. People buy them out of necessity, not because they want the product. So it's passive buying," Matsuzaki said.

"Then I thought I should make something people want to buy. Even though we are faced with this strong headwind at home, I thought I should spread the tradition more."

He decided to digitalize "dual hanko," or wooden stamps on which non-Japanese names are engraved in both Japanese kanji characters and the alphabet, and sell them as images online. Bunbukudo Inbo had sold around 800 wooden stamps since the launch of the series in 2017. Going digital, he thought, would require no visit to the shop with no risk of coronavirus infection.

Every hanko design is unique because he creates it based on a customer's choice of font and kanji characters that sound close to the original foreign name. Prices range from 2,750 yen ($25.70) to 3,300 yen, and Matsuzaki hopes the digital stamps can be used for various purposes, including profile pictures on social media.

It is still uncertain how the debate over the hanko tradition will unfold and what it would mean to shops like Matsuzaki's in the long run. At Bunbukudo Inbo, sales of Japanese hanko seals far exceed those of dual ones, but he says both are necessary.

Matsuzaki, who has not groomed anyone to take over from him in the business, is determined to keep his hanko shop, inherited from his father, open for decades to come.

"Without the coronavirus, I'd never gotten the idea of digitalizing dual hanko. And because of hanko seals, I'm here," he said.

"I will have to explore what I can offer as a hanko shop to society in the new era. I may even get more exciting ideas."

Related coverage:

Japanese university ends seal-stamping custom to promote telework

Japan to review seal-stamping custom to better contain coronavirus

University students launch COVID-19 multilingual support project

By Noriyuki Suzuki,

By Noriyuki Suzuki,