While artificial intelligence has started to outmatch masters of the Japanese board games go and shogi, the sport of curling, known as chess on ice, is also turning to high technology in search of the ultimate strategical advantage.

An autonomous engineering research group from Hokkaido University gave a lecture on how AI could impact the game of curling as the sole Japanese representatives at a research forum on the use of AI in team sports held in New York in February.

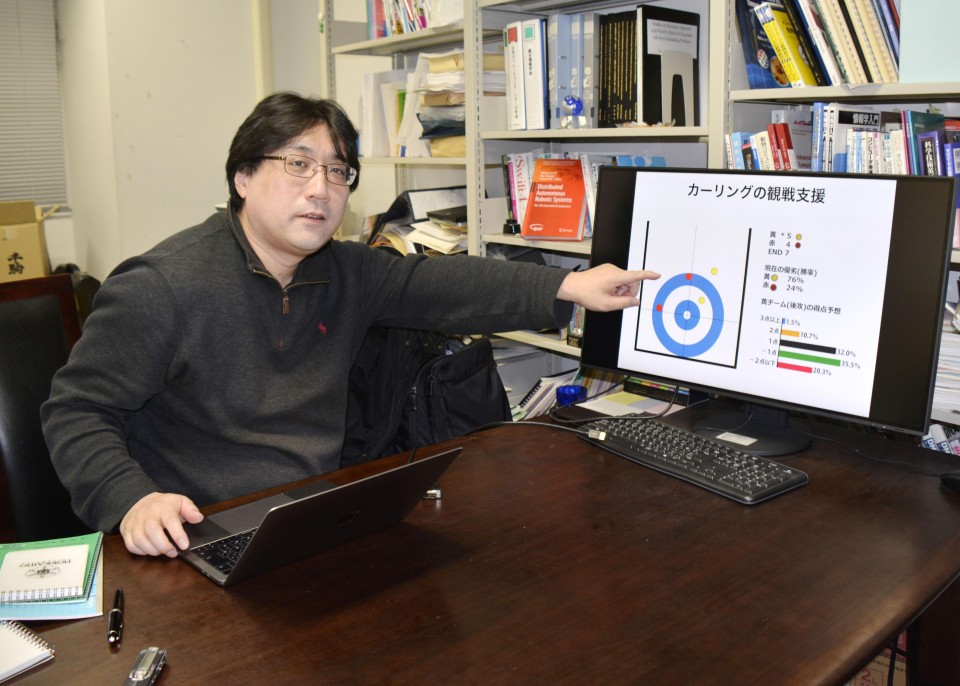

The team, including 51-year-old graduate school professor Masahito Yamamoto who has been developing the system for the past six years, had AI learn 1 million patterns of curling stone movement and scoring situations through playing games against an AI opponent.

Related coverage:

FOCUS: 5G expected to drive new businesses, spark tech advances

Based on countless game simulations, the AI system is able to derive the best possible shot options from among around 10,000 possibilities -- calculating scoring chances, changes in winning percentage and risks of missing shots -- to provide a statistical framework behind decisions that increase the probability of victory.

"Going through tens of thousands of throws might see the AI come up with something that is beyond human thought," Yamamoto said of the system's possible impact on the winter sport in which teams pursue points by sliding stones across a sheet of ice with the aim of placing them closest to the target.

The women's bronze final during the 2018 Pyeongchang Olympics saw Japan lead Britain 4-3, entering the 10th and final end. Britain, throwing second, appeared to have had a relatively easy, if risky, chance to take two Japanese stones out and claim the victory with the end's final shot.

Japan's Satsuki Fujisawa, the foursome's skip, said she "thought we lost" when Britain drove for the two-stone takeout rather than playing it safe with a draw for one point that would have sent the match into an extra 11th end with the European team throwing first, which is a disadvantage.

Britain's shot proved disastrous, however, as it pushed a Japanese stone closer to the target and handed the Asian team a 5-3 victory and its first Olympic medal.

Although it appeared to be a dramatic finale to many, Yamamoto's AI later predicted Japan had a 74 percent winning chance to Britain's 26 percent before the final throw.

"AI calculated that Britain was in a difficult position to try to score two points by taking out those stones," Yamamoto said.

"Tactics could change for curlers should they better understand the big drop in winning percentage in cases where they are slightly off with an ideal shot," Yamamoto said.

Unlike in go and shogi, the latter known as Japanese chess, in which players can execute exact game plans, curlers need to be precise and able to play shots on a surface that can change due to myriad factors. AI can only play an important supporting role, stresses Yamamoto.

"AI's purpose is to help them tactically," Yamamoto said.

In principle, AI could provide a guide for curlers at the intermediate level. Its practicality on ice could also be enhanced by taking into account data on the distinctive sweeping of ice in the sport, which is done to help stones travel farther and curl less by creating frictional heat on the ice in the stone's direct path.

There are systems also developed for AI that rate soccer and ice hockey players based on their movements and contributions, and Yamamoto believes its impact will only grow.

"Sports that do not incorporate technology may die out one day. Those that lag in taking it up may find themselves on the outside when it comes to the Olympics," he said.