For the past several years, a 98-year-old former Japanese soldier who was interned in a Siberian labor camp at the end of World War II has been recounting his experiences to schoolchildren to encourage them to value peace.

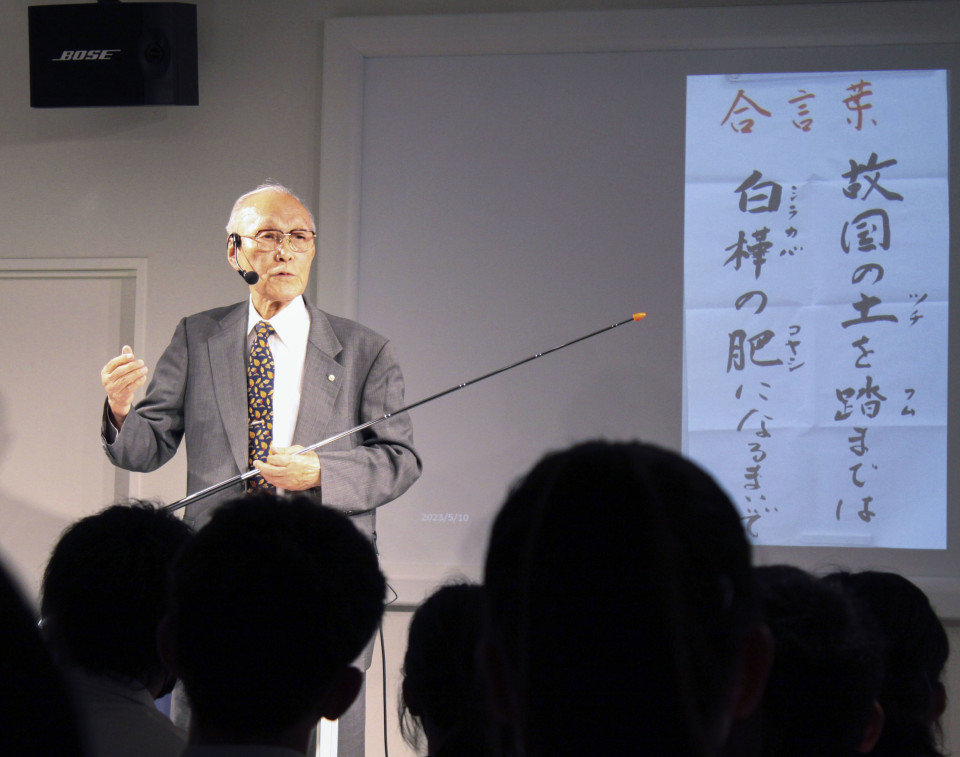

"I hope you will carry the future with you so peace will endure for a long time to come," Masaru Nishikura, of Sagamihara in Kanagawa Prefecture, told a group of visiting junior high school students last month at the Memoril Museum for Soldiers, Detainees in Siberia, and Postwar Repatriates in Tokyo's Shinjuku Ward.

The around 40 third-year students from Toin Daiichi Junior High School in Toin, Mie Prefecture listened quietly as the usually mild-mannered Nishikura spoke with controlled passion for about an hour.

"All of you who will become adults and maybe have your own families one day, please make sure your children and grandchildren never have to endure hardships like I did."

The eldest son in a farming family in Niigata Prefecture, Nishikura went on active duty in the Imperial Japanese Army in January 1945.

He was stationed near the border of what is now North Korea and Russia when Japan surrendered in WWII and was interned by the Soviet Union in a labor camp in the Komsomolsk-on-Amur region of Siberia.

Close to 600,000 Japanese soldiers are believed to have been held in Soviet labor camps in the wake of Japan's defeat in the war. They were interned for up to 11 years, with about 55,000 dying as a result of the work they were forced to do, the severe living conditions and malnutrition.

In the talk, which took place on his birthday, Nishikura spoke of a time when a pickaxe he was using bounced off the frozen earth during winter construction to try to bury water pipes. "I won't forget that even in death. It was brutal," he told the audience.

He also remembered that, dogged by hunger, he picked up a "frozen potato" from a road one day only to discover it was actually horse dung when he later thawed it out.

One middle school student asked what he did in his free time. "I had about one day off a week to do laundry," he replied. "We weren't allowed to go outside and meet ordinary citizens. There was nothing fun about it."

After listening to Nishikura, Riona Ito, 15, said, "It was the first time I learned about the hardships of internment. When I return home, I want to tell my family about Mr. Nishikura's experiences."

Nishikura was repatriated in July 1948. Initially, he refrained from talking about his experiences because "it was something that I dared not speak about," he told Kyodo News in a phone interview.

But Nishikura, who worked at an insurance company as a pension consultant for about three decades, was encouraged by a customer to give a speech about his internment experience when he was considering retirement.

After he was approached by the Memorial Museum, which organizes storytelling by war survivors for schools that wish to hear them, he began to tell his story in August 2017 at the age of 92.

Nishikura also conducts virtual talks from home and has appeared online at five schools, such as Okinawa Prefecture Yokatsu High School in Uruma, Okinawa. He finds the dialogue stimulating, saying, "There are many teachers and students eager to learn."

He smiled for commemorative photos with the Toin Daiichi Junior High School students after wrapping up his talk. As a birthday gift, the museum's curator presented Nishikura with a flower bouquet and messages written on special Japanese paper.

"I want to keep talking about this as long as they continue to ask me," Nishikura said.