TOKYO - Olympic Movement stakeholders face a challenge to strike a balance between embracing activism in sports and preventing the games from turning into a stage for political demonstrations in Tokyo next year amid a surging protest movement against social injustice.

Douglas Hartmann, a professor and chairman of the Sociology Department at the University of Minnesota, argues that society is becoming more tolerant about athletes' involvement in protests and activism, and the trend is likely to affect their behavior at the upcoming Tokyo Games.

"This is awareness, new levels of awareness about anti-blackness, about police brutality to African Americans, about institutional racism. I do think in the sports world, there has been a build-up of activism and awareness over the last decade," he said in a recent phone interview with Kyodo News.

In May, George Floyd, an African American man, died after being arrested by police officers in the U.S. city of Minneapolis, reigniting the Black Lives Matter protest movement, which initially began in response to the shooting death of black teenager Trayvon Martin in Florida by a neighborhood watch volunteer in 2012.

Another police shooting of a black man, which happened in Wisconsin in late August, prompted the National Basketball Association and Major League Baseball to suspend some games due to protests by athletes against the incident.

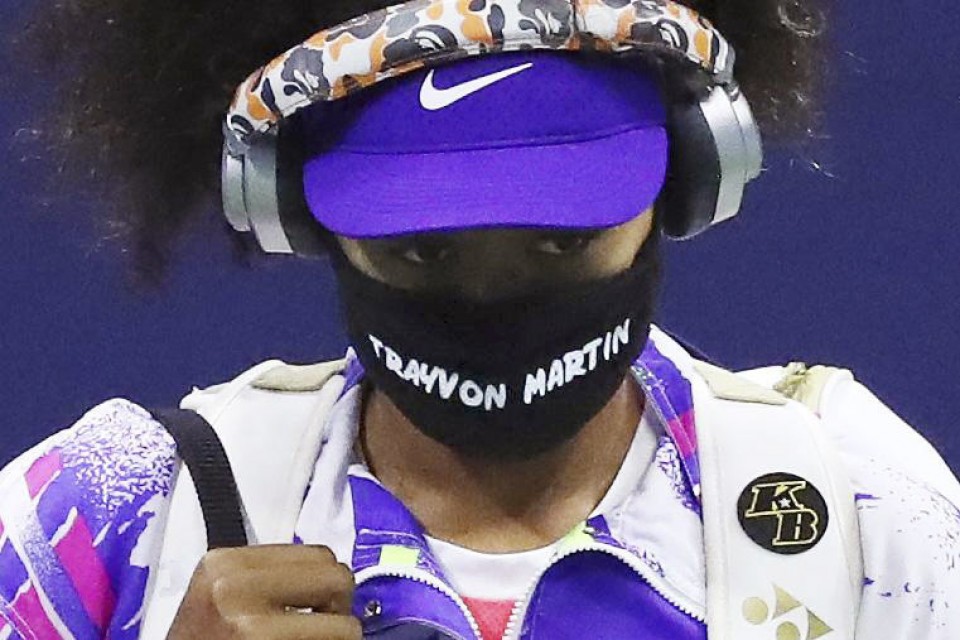

Tennis star Naomi Osaka, who has a Japanese mother and Haitian father, wore seven face masks before as many matches with the names of victims of anti-black racism or police violence to raise awareness about social injustice, en route to winning her third Grand Slam title at the U.S. Open.

"(W)e witnessed athletes across the country demand change through both words and actions -- showing they are a powerful force in the community," said Sarah Hirshland, CEO of the U.S. Olympic & Paralympic Committee, as the USOPC and the Athletes' Advisory Council convened the Team USA Council on Racial and Social Justice in late August.

Earlier this year, the committee's advisory council, in partnership with John Carlos, the men's 200-meter bronze medalist at the 1968 Mexico Games who gave a Black Power salute on the podium with fellow U.S. athlete and gold medalist in the event Tommie Smith, also called on the IOC to scrap the Rule 50 guidelines regarding the neutrality of sport and the Olympic Movement.

The Olympic Games, regarded as a "festival of peace," has been trying to stay neutral and free from politics, but the two appear to have been intertwined with each other throughout history.

Carlos and Smith were both banned from further Olympic activities, but their gesture remains one of the most iconic Olympic images, leading to their induction into the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Hall of Fame.

Rule 50 of the Olympic Charter states, "No kind of demonstration or political, religious or racial propaganda is permitted in any Olympic sites, venues or other areas," although it allows athletes to express opinions in interviews and on social media.

The council has called on the International Olympic Committee and the International Paralympic Committee to come up with a new policy that protects athletes' freedom of expression at the Olympics and Paralympics, in collaboration with athlete representatives.

IOC President Thomas Bach declared at an IOC session in July that "solidarity and non-discrimination are in our DNA."

"To reconcile these values of free expression on the one hand and respect for each other on the other hand, the IOC Athletes Commission has initiated a dialogue among athletes on how they can even better express their support for the Olympic values in a dignified and non-divisive way," he said.

Meanwhile, Hartmann pointed out, "I think the real problem they have is how far they are willing to go for that speech, gestures or demonstrations to take place on the field of competitions, in the ceremonies, any official ceremonies whether it's the opening ceremonies or the medal ceremonies."

The IPC has said its athletes' council has begun discussions with individuals related to the Paralympics around the world on how athletes can express their protests against social injustice and opinions on the matter.

Under the current IPC rules for the Paralympic Games, athletes are free to express their views on any subject on social media and when speaking to the media. However, they are not allowed to use the field of play or podium to protest, according to the IPC.

"Many of the protests and demonstrations around the world in recent years, whether they be about race or gender equality, are based on the fight against discrimination, a daily fight that all persons with disabilities are familiar with as they are part of the world's largest marginalized group," said Chelsey Gotell, chairwoman of the IPC Athletes' Council.

"As an organization that is committed to driving social inclusion and advancing human rights, it appears logical for the IPC to allow protests around discrimination at the Games," she said.

Nevertheless, she added that "the whole area of Games protests is something of a Pandora's box."

Hisashi Sanada, a professor in the Faculty of Health and Sport Sciences at the University of Tsukuba, is cautious about permitting protests at Olympic and Paralympic venues as he insists such acts can become a double-edged sword due to the high-profile nature of the games.

"They will be highly effective, but they can pose negative impacts as well. It will turn the Olympics into a completely different event...political activities disguised as a sporting event," said Sanada, who also serves as a counsellor to the CEO of the Tokyo Organizing Committee of the Olympic and Paralympic Games.

"Protest should be basically conducted away from the games and the venues, such as on social media, among others. That type of protest should be allowed during the Tokyo Games," he said.

Both Sanada and Hartmann said it will be extremely difficult to distinguish what is political and what is not in terms of allowing athletes' protests at the venues.

Hartmann suggested a potential solution for the IOC to find common ground with the athletes is to redefine today's protests as a moral stance on human rights issues.

"I still think it's going to be extremely difficult for them to allow gestures that call attention to race on the victory stand, for example...but I do think they will kind of accommodate and probably end up trying to redefine certain acts of activism or certain social issues as either human rights issues or larger moral issues," said Hartmann.

"Those are really hard things... (to) find consensus on in a global world where we really do have pretty profound cultural differences that separate nations and peoples," he said, while admitting that the definition of human rights itself is a debatable issue.

The IOC Athletes' Commission has indicated it will formulate a final proposal by next March after discussing the matter with athletes around the world and submit it to the executive board.

By Takaki Tominaga,

By Takaki Tominaga,