Japanese ritual morticians who use highly-specialized skills to restore bodies that have been severely disfigured in accidents or even murders have long been underappreciated for the work they do for grieving families.

Because there is neither a certification system nor standardized techniques in the profession known as "nokanshi," the services provided by morticians such as Chiemi Tsunoda are often misunderstood or neglected by Japanese funeral homes. Kyodo News visited one to investigate how the intricate and important work is carried out.

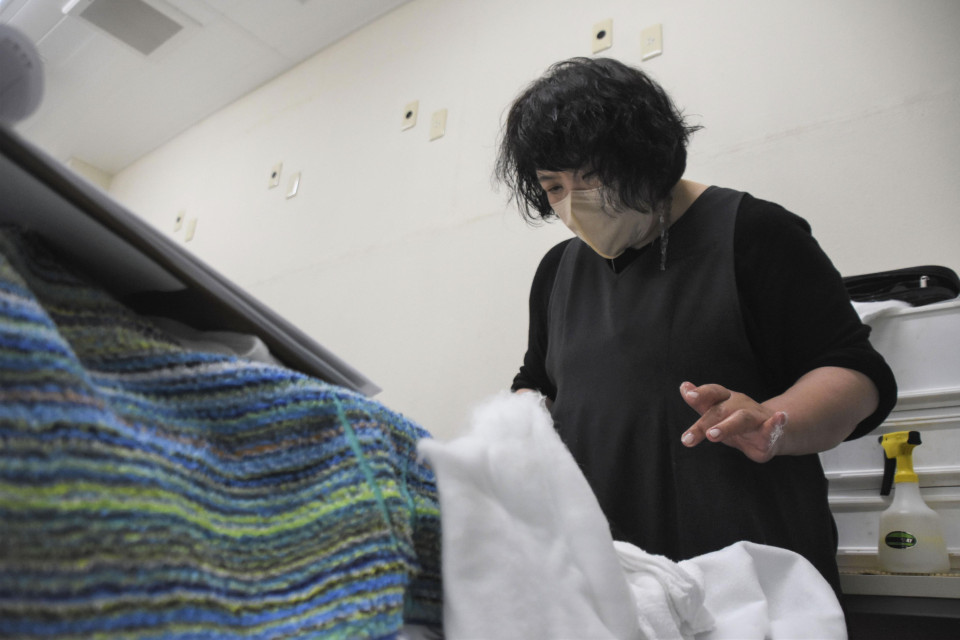

Tsunoda, 56, who plies her trade with Tokyo firm Toubi Co., uses special waxes and nearly three decades' worth of experience to restore some 100 bodies for viewing each year so families can "greet, touch and say goodbye to their loved ones."

In March, the bodies of four men and women lay in the company's facility where the room temperature is kept at just 12-13 C.

Toubi, which received the requests to restore the corpses from the bereaved families, handles a variety of death situations, including train accidents, suicides and people who die alone and are not found for an extended period.

Tsunoda promises each family member that she will restore the body "the way the person was." In this instance, she applied layers of wax to the dry, chapped face of a woman in her 80s who has been dead for roughly a month, bringing fullness back to her cheeks.

"I see you have a mole here," Tsunoda says, speaking to the dead woman as if in a conversation, comparing her lifeless face with a photo in which she is smiling softly.

The deep wounds on other bodies are closed using an adhesive bond, while indents in foreheads and noses are reshaped using cotton. With their hair neatly coiffed and makeup applied, their faces take on a tranquil look.

The term nokanshi grabbed the spotlight due to the 2009 Oscar-winning film "Okuribito" (Departures). The Japanese drama, which won an Oscar for best foreign language film, is about a young man who mistakenly -- and to his horror -- takes a job as a ritual mortician through a job advertisement.

The film delves into the topic of death, often avoided and viewed as taboo and "unclean" in Japanese society.

It touches on the universal theme of dignity in death in a solemn, mysterious and sometimes humorous manner through the eyes of its protagonist, who makes his living preparing the deceased for cremation despite facing ostracism from family and friends in a rural Japanese community.

As detailed in the film, the job's primary duties entail cleaning the bodies, dressing them in white clothing, applying makeup and placing them into a casket. Tsunoda says Toubi goes the extra mile to repair extensive damage to bodies. It receives a steady flow of business through funeral homes from families of people who have died in Tokyo and its surrounding areas of Saitama, Chiba, and Kanagawa.

Tsunoda, now a veteran in her own right after 26 years in the business, saw a job advertisement to become a nokanshi when she was 29 and employed in a part-time job. She decided to make a switch to become a full-time ritual mortician.

But what convinced her to master the craft was a murder victim she dealt with several years ago. The female had been dead for a long time resulting in significant bodily decay and leaving no trace of her former self. "I made a promise to restore any corpse no matter what state it was in," Tsunoda says.

She became utterly absorbed in the task she faced for two days. Although Tsunoda never met the family in person, when she returned the body to them in Tokyo, she could hear a voice from behind a curtain say, "It's her!" and tears welled up in her eyes.

"By looking at someone's face and saying goodbye, they will feel no regret. Even if they are sad now, there will come a time when they can look ahead and move on," Tsunoda says.

According to Toubi, since there are no public qualifications or uniform standards to become a ritual mortician, funeral homes working with bereaved families may be reluctant to explain such services due to a lack of understanding, resulting in bodies that could have been restored being left untouched.

To improve the current situation, Toubi is working to establish cooperation among ritual mortician contractors, establish industry-wide techniques and train future workers.

Yukihiro Someya, the 56-year-old company president, hopes to raise the public profile of the profession so people have greater opportunities to express their gratitude to those who have passed away.

"We send our loved ones off, and one day, we will be sent off too. We want to make this process something that makes people feel warm inside," Someya says.

Related coverage:

FEATURE: Asian fans flock to "Crash Landing" hit drama site in Switzerland

FEATURE: Anime "Slam Dunk," "Suzume" locations in Japan a magnet for tourists

FEATURE: Japan firms ready to take bite out of booming Chinese pet market

By Narumi Tateda,

By Narumi Tateda,