An ongoing collaboration between a distinguished bilingual "rakugo" artist and a University of Cambridge professor is resurrecting popular culture from Japan's Edo period never before seen by contemporary audiences.

By doing so, the pair hopes to expand the repertoire of rakugo, a traditional Japanese form of comedic storytelling, making otherwise obscure aspects of Japanese literary and cultural heritage more accessible to the general public.

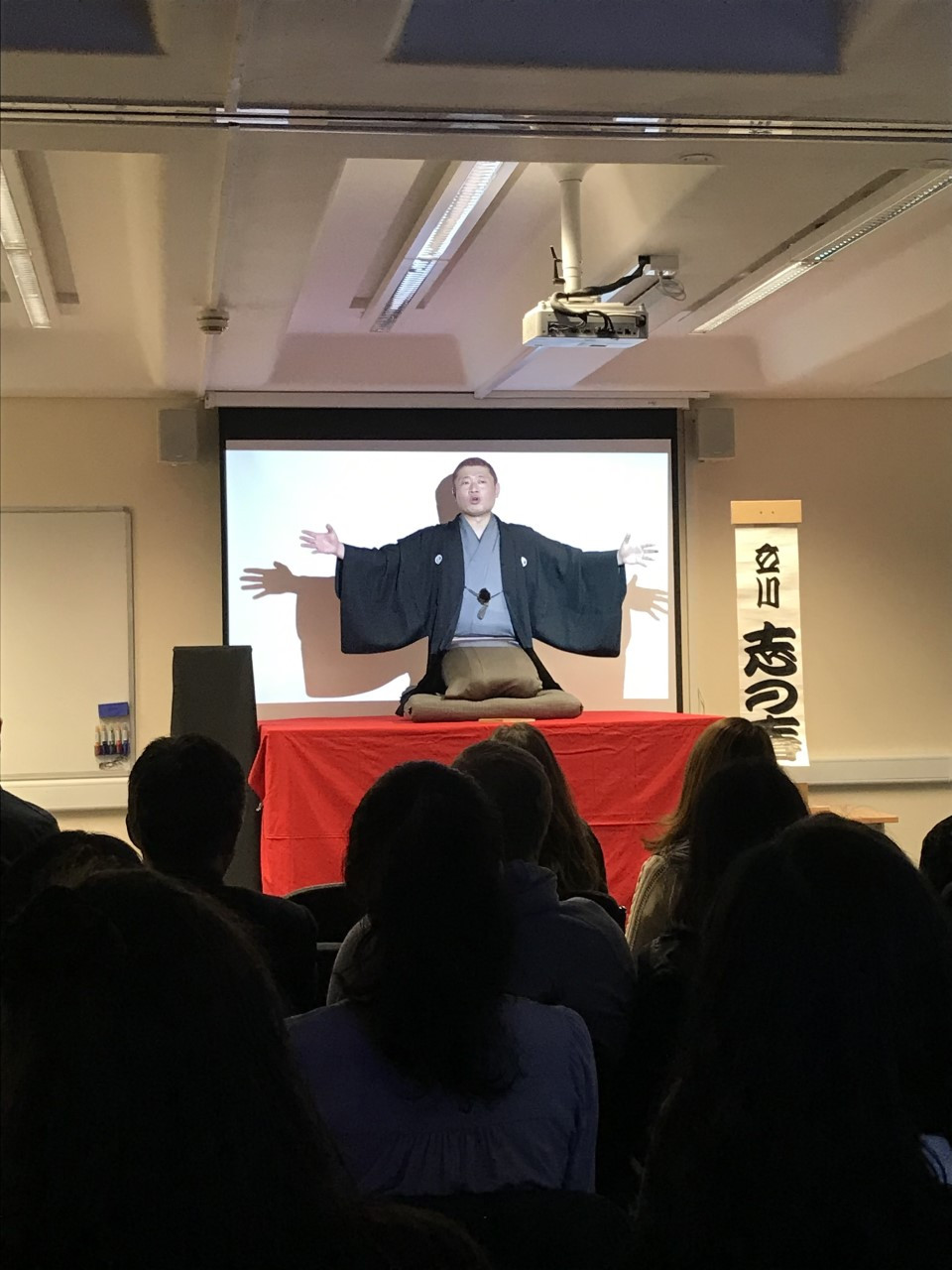

In February, Tokyo-based rakugo master Tatekawa Shinoharu held an online Japanese performance for the students at Cambridge's Faculty of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies and his Japanese fans.

For the event, he unveiled new work commissioned by Laura Moretti, a professor of early modern Japanese literature and culture, based on a fictional character at the heart of her research: the colorful quack doctor Chikusai, who enjoyed great popularity between the 17th and 19th centuries.

It is only the latest project between Shinoharu and Moretti, which marries the long-standing rakugo practice of creating original works and the art form's roots in the Edo Era (1603-1868).

For Shinoharu, 46, who has a devoted fan base and a YouTube channel where he performs rakugo in both English and Japanese, creating new works in both languages came naturally from having witnessed his master Tatekawa Shinosuke constantly invent new material to differentiate himself from other performers.

So when Moretti approached him with the idea of turning never-before-seen Edo-period material into rakugo, he was intrigued by the opportunity.

Moretti is a leading expert in Edo-period pop literature and culture and a specialist in "kuzushiji" -- a difficult-to-decipher cursive script in which most Edo-period materials are written.

Since specialist training is now required to read, transcribe and translate kuzushiji manuscripts, the materials Moretti works on and adores are often just as unfamiliar to the Japanese public as they are to foreign audiences.

While thinking about how to make the material reach a wider audience, Moretti came across Shinoharu and saw his willingness to explore new frontiers of rakugo when he performed for her students online for the first time in 2020.

Witnessing how well he communicated rakugo in English and Japanese, she felt he would be the perfect performer to bring these works to life.

There was one character in particular whose voice Moretti longed to hear: the bumbling Chikusai, who often covers up his medical failures with wit and wordplay.

Despite appearing as the beloved protagonist of multiple texts throughout the Edo period -- sometimes as a miraculous healer instead of a quack -- Chikusai did not survive in pop culture after the 19th century. Moretti argues this may have been because the rise of Western medicine made the stories go out of vogue.

"Chikusai is one of the loves of my life. I thought (he) had all the right ingredients to become a rakugo piece, and for some reason this guy didn't make it into classic rakugo...So why not make him into rakugo now?" Moretti told Kyodo News in an interview.

A traditional form of entertainment with 400 years of history, rakugo (literally meaning "fallen words" in Japanese) features a lone storyteller or rakugoka sitting onstage and performing comical, sentimental or tragic narratives from memory.

Characteristically heavy in dialogue, the "rakugoka" performer delivers these stories using slight turns of the head and changes in tone, pitch and body language to portray multiple characters.

Today, there are around 1,000 professional rakugoka in Japan. And out of 500 "living" rakugo stories in the classic Edo-period repertoire, 100 are performed regularly in theaters nationwide, according to Moretti.

With such a small repertoire, it is no wonder that renowned rakugoka often create original works to distinguish themselves. Shinoharu is one master who revels in this challenge.

Born in Osaka Prefecture as Ittetsu Kojima, he grew up between Chiba near Tokyo and New York, becoming bilingual and eventually studying at Yale University.

However, while working in Tokyo as a graduate, he fell in love with the rakugo of Tatekawa Shinosuke, whose performance he saw because he recognized him as a well-known television emcee.

Speaking with Kyodo, Shinoharu said convincing his master to accept him as his apprentice in 2002 was not easy, and that neither was the traditional Japanese apprenticeship he had to endure.

After starting training late at age 26, it took him 17 years to become a "shinuchi" -- the highest rank a rakugoka can achieve and the point at which they can take their own apprentices.

Due to his upbringing abroad, he struggled with the subservient, unquestioning attitude required of him as Shinosuke's apprentice, meaning that his master had to "tame" him before he could even begin teaching rakugo.

Having no amateur experience made the training process of copying every single word and pause in his master's oeuvre even more difficult. But it was this very quality that gave him the resilience to complete his "marathon-like" apprenticeship, he says.

"My master had a lot of difficulty with me I can assume...all he told me for the first three years was that I had no talent," Shinoharu said. "If I were brought up purely in Japan, I would have received those words completely and quit...but being raised in the U.S. had its good points, because my self-esteem was high enough not to be crushed by that."

He also said that his lack of amateur experience meant he had no pre-existing pride as a rakugo performer, making it easier to immerse himself and eventually replicate his master's style.

A distinguished master in his own right now, Shinoharu performed the new works about Chikusai and his devoted servant Niraminosuke's misadventures for the first time in person during an April 2022 visit to Cambridge, which Moretti says "made my dream come true."

"I cried the first time I heard his voice," she said. "I have studied this fictional character for the best part of ten years, so I felt very emotional that the material still entertains in the 21st century. He's not completely dead!" she said.

Shinoharu says creating new rakugo from Edo-period books was an exciting process for him but that making the irresponsible Chikusai a likable character for modern audiences was also challenging.

"Chikusai tries to pretend he's good where he's not, and those characters can be easily hated," he said. "To form a charming character who makes mistakes, but who you can laugh at and forgive, was key for that story to become rakugo."

Now, Shinoharu is starting to integrate the same Chikusai rakugo into his regular repertoire for Japanese audiences, as demonstrated by February's online performance.

Shinoharu and Moretti plan to continue their new rakugo collaborations, starting with Shinoharu's next visit to her annual kuzushiji summer school later this year.

"The collaboration is a great source of inspiration for me -- if I'm just searching for materials myself, it's going to be very limited. But when I learn new things (from Moretti), something lights up in my brain, and something gets created. And that's always very welcome," Shinoharu said.

Related coverage:

FEATURE: Ghibli film inspiration enlivens French tapestry tradition

By Rosi Byard-Jones,

By Rosi Byard-Jones,