English-language readers are now able to appreciate 100 classical poems by Emperor Meiji (1852-1912) thanks to over 30 years of translation work by Harold Wright, a U.S. scholar of Japanese literature who was a student of the late Japanologist Donald Keene.

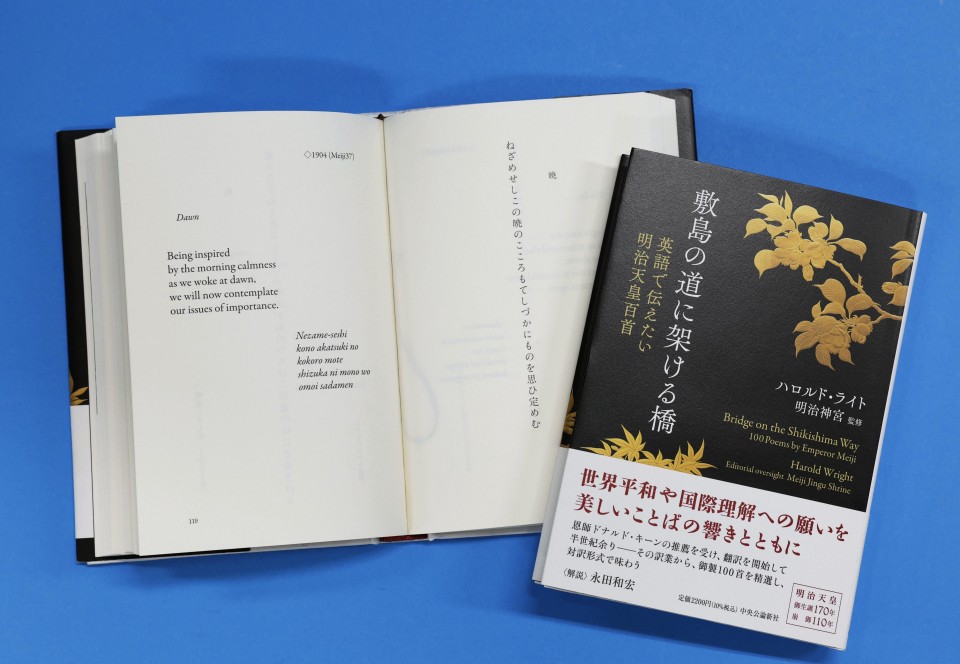

The collection of poems in "Bridge on the Shikishima Way," released last month in Japan, brings to life the feelings of an emperor who lived in an era when tradition and modernity intersected, with Japan transforming from a feudal state during his reign.

"Emperor Meiji was not only a thoughtful emperor to his people, but also a gifted poet...(who) felt deeply that the world should live in peace with deepened feelings of international understanding," said Wright, who is now a professor emeritus of Japanese language and literature at Antioch College in Ohio in the United States.

This year marks the 110th anniversary of the death of Emperor Meiji, who, during his lifetime, composed around 100,000 poems, many of them containing a wish for peace.

One particular poem lamenting the outbreak of war between Japan and Russia in 1904 is said to have moved then U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt, who led the signing of the Treaty of Portsmouth that formally ended the Russo-Japanese war the following year.

The poem was read by Emperor Hirohito, the grandson of Emperor Meiji known posthumously as Emperor Showa, in September 1941 to express his desire for peace at a conference involving Japanese government and military leaders in which Japan decided it was prepared to enter into war against the United States, held just three months before the Pacific War began.

In addition to prayers to the gods -- a tradition of the imperial family -- the 100 "waka" poems include sentiments about international goodwill and war, as well as the lives of the people, with some rich in emotion.

Waka poetry was developed by the court aristocracy in the sixth century. A "tanka" poem, which is typically synonymous with waka, consists of 31 syllables in a pattern of 5-7-5-7-7.

The idea of translating imperial poems into English first came in 1964, the year of the first Tokyo Olympics. Shinichiro Takasawa, who would later become chief priest of the capital's Meiji Jingu shrine dedicated to Emperor Meiji, wanted to welcome international guests with a few poems by the emperor and his wife Empress Shoken as some games-related events would be held on the grounds of the shrine.

When consulted, Keene introduced Wright, who was a Fulbright scholar of Japanese poetry at Keio University at the time, as a translator. In 1982, Wright received a fresh request to translate more manuscripts of imperial poetry, later working on them while tenured at Antioch.

Wright extensively researched Japanese history, culture and religion in the process, striving to remain faithful to each poem's original rhythm while maintaining a balance between meaning and imagery in a way consistent with the foundations of English poetry.

Each poem took several months, and in some cases even up to a year, to translate, with Wright repeatedly reading aloud both the original Japanese and English translation when finished to check its cadence.

"The main feeling I had when I completed the translations was a deep feeling of gratitude for being able to at last finish, at this advanced age, the important work I was asked to do so many years ago," said Wright, who turned 91 this year.

Kazuhiro Nagata, a waka poet and cell biologist, in his commentary for the book said it would help spread knowledge of the traditional poetic form and its long history, one "supported by the imperial family and the people of Japan alike."

"That is to say, this opportunity for readers around the world to experience the roots of Japan's culture should be of tremendous significance," Nagata said.

Related coverage:

Japan's emperor hopes for end of coronavirus pandemic in poem ceremony

Imperial couple yearn for end of pandemic in postponed poem ceremony

Emperor Hirohito stopped from expressing remorse over war