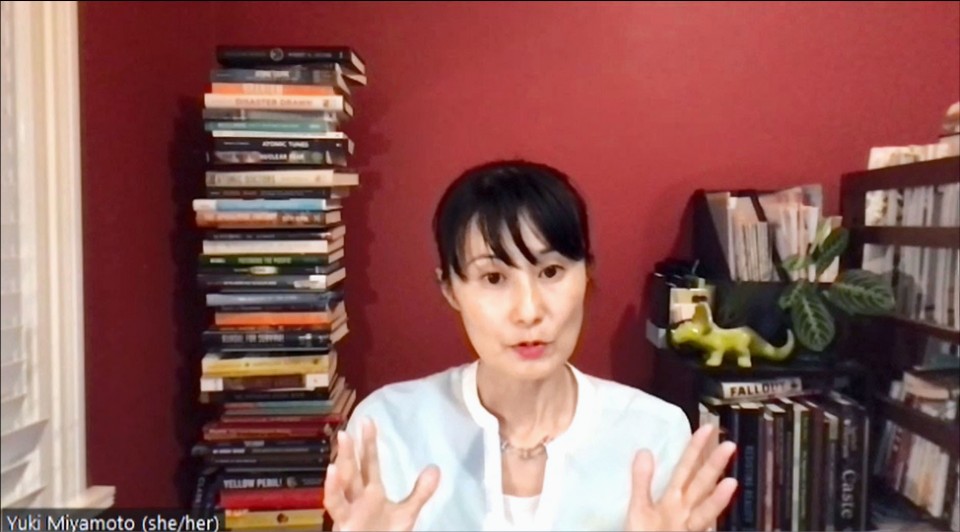

For nearly two decades, Yuki Miyamoto, a professor and second-generation Hiroshima "hibakusha," or atomic bomb survivor, has tried to teach her students at an American university about the terrible toll nuclear weapons take.

Perplexed by the justifications given in the United States for dropping the bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, she traveled to the U.S. to pursue studies in ethics where her work now mainly focuses on nuclear discourse at DePaul University in Chicago.

Today, she says many still believe what she considers a "myth" that the A-bomb helped save many American lives by hastening the end of World War II and the majority show little interest in nuclear issues.

But some of her students do not fit that mold and are decidedly against nuclear weapons. They see them as inhumane objects of destruction, Miyamoto, 54, explained.

She said that since her first lecture in the U.S., she has told students, "I will not teach you what is correct." This is because Miyamoto wants students to conclude on their own that nuclear weapons should be abolished.

Her mother survived the atomic bombing. From the time Miyamoto was little, there had been protests by hibakusha over nuclear testing, but as she grew older, she saw that such reactions "failed to resonate" with the American public.

At the age of 27, she headed for the United States. Since 2003, when she began lectures explaining the horrors of the atomic bomb, she has debated students who justify the bombings as necessary to bring an end to the war. Almost every other year since 2005, she has led her students on field trips to Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Miyamoto said in her lectures and seminars, "Most start off being apathetic." Although the U.S. has conducted over a thousand nuclear tests, when asked to guess at the figure most of her students respond in the single digits. Some have taken offense at subjects critical of the United States.

In her analysis, an image has formed among U.S. citizens from the media's expression of nuclear weapons and nuclear power as "symbols of power" and "control."

She says cultural artifacts like comic books where the "superhero" who saves the day with powers derived from a brush with a radioactive substance, ingrains the idea that strength and nuclear narratives are inextricably linked and not harmful.

Miyamoto also pointed out what she believes is an uncomfortable truth that the U.S. military provides "welfare" by subsidizing university tuition in exchange for enlistment, but she suggests that such criticism is "taboo" in a country that venerates its military as unimpeachable.

She is convinced that these "deep-rooted" factors are behind the theory of the justification for the atomic bomb and that they also hinder understanding of the negative aspects of nuclear weapons. Miyamoto's lectures, she says, serve to remove such psychological barriers that have unconsciously been thrown up.

Jade Ryerson, 23, a student of Miyamoto's who has attended her seminars and field trips to Japan, said even though she did not know a lot about nuclear weapons before her trip, "I was definitely aware that this could happen. What we've been told is that it was to end the war, but from engaging in that class and learning more about history we know that there is a lot more to it."

When asked about the most horrifying images that come to mind after visiting the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, she said, "I remember photographs of the medical impacts such as the severe burns one man sustained all along his entire back...I don't know how anyone could look at images like those and not believe that nuclear weapons are unethical."

Saira Chambers, 39, another student who has taken part in the field trips, held her own exhibition in 2016 in Chicago to educate people about the destructive nature of nuclear weapons.

Chambers supports the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons' goal to ban the weapons, a treaty to which neither the United States nor Japan is a party, as she says the status quo based on nuclear deterrence is "too dark a world" to live in.

When asked how she thinks Americans can be swayed to believe a world without nuclear weapons is preferable, Miyamoto said arguments detailing the destruction nuclear explosions wreak on the natural environment can be persuasive, as can the impact radiation has on women's bodies. This, in itself, should be enough, Miyamoto said.

Through her lectures, she hopes to convey the message that nuclear weapons as an environmental threat are "closely linked to the values considered most dear to Americans."

Related coverage:

A-bomb survivor says Japan PM's nuclear speech avoided "honest debate"

FOCUS: Role in Japanese war machine made Hiroshima, Nagasaki A-bomb targets

Texas univ. holds graphic photo exhibition of Japan A-bombed cities

By Hiroshi Inoue,

By Hiroshi Inoue,