In the 150 years since American educator Horace Wilson began teaching his students in Tokyo about baseball in 1872, the game's meaning to Japanese and the impact of this nation's brand of baseball on the world have changed dramatically.

During that time, Japan has become a great baseball-playing nation, producing unique talents such as Hideo Nomo, Ichiro Suzuki, Shohei Ohtani, and now Roki Sasaki.

How Japan went from a newly unified nation with no sporting tradition beyond the martial arts to a world baseball power is a tale of curiosity for foreign ideas, national identity, authoritarianism, and commercial exploitation, but most importantly, passion.

Over the years, Japan's changing political goals, and economic and social circumstances, have all left their imprint on the game that became known as "yakyu" or field ball.

Imported incidentally as accompanying baggage with the foreign learning needed to strengthen Japan and allow it to fend off Western imperialist intrusion, baseball became a beacon of hope when a schoolboy team soundly beat teams of American adult expats in 1896.

At the same time Japan pushed to stifle democracy at home and expand imperial influence in East Asia, liberal elements in baseball were more and more brought to heel in pursuit of "pure Japanese" sensitivities.

A post-World War I economic boom opened the door for professionals, while World War II's end introduced veterans, whose coaching added military-style physical discipline to the mix of an increasingly top-down regimented endeavor.

More recently, increased interaction with America's major leagues has given players more choices, while declining birth rates and changing social norms have changed the way Japanese see the game's century-old win-at-all-costs mentality.

That mentality came to baseball accidentally, stemming partly from the success made by Japan's first national baseball heroes, 24 years after Wilson introduced the game.

The team from "Ichiko," the academically elite First Higher School of Tokyo, was an organic grass-roots endeavor that adopted some Western ideas that came with the new sport and wed them to the ethos of Japan's feudal era warrior code.

The treaty port of Yokohama hosted Japan's first games at least as early as 1871 between American merchants and U.S. Navy sailors. The first Japanese team, the Shimbashi Athletic Club, was formed by American-trained engineer Hiroshi Hiraoka in 1878, among employees of Japan's first railroad, between Yokohama and Tokyo's Shimbashi.

Ichiko's victories over Yokohama-based teams of American adults, sometimes bolstered by sailors, ignited a Japanese interest in the game that remains bright.

Japanese flocked to watch this sports phenomenon, but change was in the wind.

Within a few years, Ichiko was displaced as a power by the Tokyo vocational schools that would evolve into Waseda and Keio universities. Influential Ichiko alumni blamed the current players for dropping the ball.

Although Ichiko's fall from grace was caused when rising admission standards steered top athletes to other schools, the players' failure was blamed on their embrace of Western liberal ideas and abandoning their predecessors' self-sacrificing approach.

Before long, baseball came under attack over the unruly behavior of players and student supporters across the country.

Waseda's 1905 American tour during the Russo-Japanese War was ridiculed as "unpatriotic," and in 1906, Waseda and Keio supporters' behavior caused the schools' annual series, then Japan's most popular sporting event, to be suspended.

A sense that baseball was getting out of hand led to a famous series of 1911 editorials called "The Poison of Baseball" that served to sell newspapers but also laid the groundwork for a "purified" Japanese game.

In 1915, the Osaka Asahi Shimbun newspaper capitalized on this to expand its readership by taking a small schoolboy tourney nationwide.

An essential element of the tournament, now the massively popular summer high school championship at Koshien Stadium, was its single-elimination competition format. This had become the norm in Japan, where travel required for far-flung schools to compete made league play unattractive.

Though no longer necessary, that format permeates Japanese sports to this day and has created an environment where the best elementary-school-age pitchers can throw five or six games in a single weekend until many of their arms give out in the name of victory and tradition.

As Japan's economy boomed after World War I, money inundated the ostensibly amateur game, sparking the rise of corporate teams around the empire and the first pro team in 1920.

That team, the Nippon Undo Kyokai, squared off for the first time against Tokyo's second pro club, Tenkatsu, in June 1923. These early teams foundered, however, after the Sept. 1, 1923, Great Kanto Earthquake left Tokyo a wrecked smoldering wasteland.

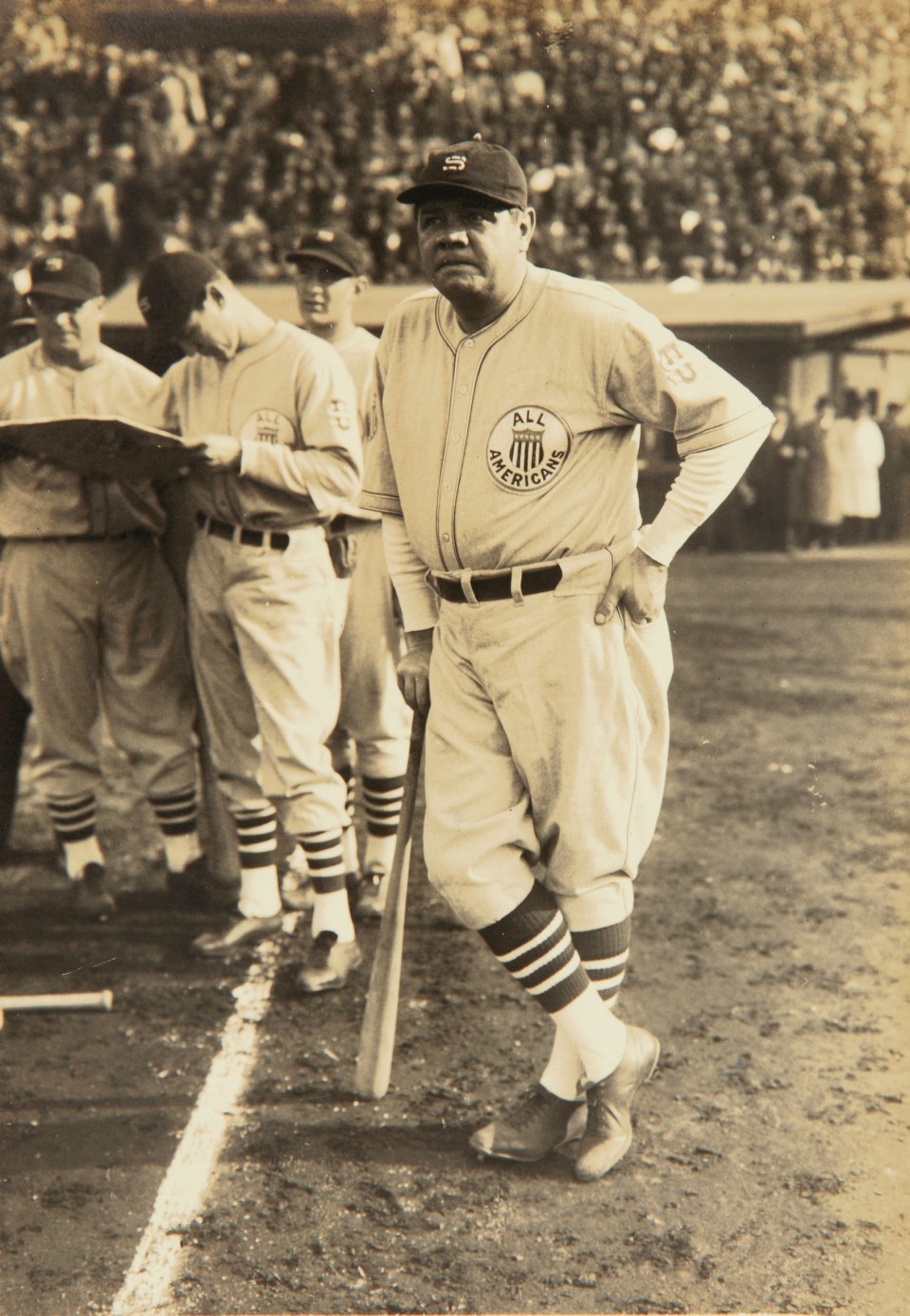

The next pro efforts didn't kick off until 1934, when Yomiuri Shimbun owner Matsutaro Shoriki invited major leaguers, including Babe Ruth. By then, Japanese amateurs were prohibited from playing against professionals, forcing Shoriki to create a pro team.

Shoriki mostly built his team from former college stars while inducing a pair of future Hall of Fame pitchers, Eiji Sawamura and Victor Starffin, to quit school. Cash persuaded Sawamura, while Starffin's recruitment may have involved coercion.

The success of the tour, and of the new pro team's subsequent tour of America, led to the creation of Japan's first pro league in 1936 with the Giants as a founding member.

That league was succeeded by Nippon Professional Baseball, which has turned a blind eye to the fact that the Nippon Undo Kyokai began 14 years before its first team, the Giants.

In 2014, NPB's official slogan was "Pro baseball's 80th anniversary" -- the Giants' 80th anniversary, even though it was the 94th anniversary of pro baseball in Japan.

But regardless of PR efforts, change continues because Japan's passion for baseball exceeds the constraints purists would impose on it. Purists had no room for Nomo's or Suzuki's unique styles, so it took an iconoclastic manager, Akira Ogi, to unshackle them from the bonds of tradition.

Shohei Ohtani only became a two-way star because his Japanese team defied the purists and convention by offering him that chance and so kept MLB teams from signing him as a teenager.

And now, as social attitudes continue to veer from post-war norms, yet more change is coming.

Some tepid pitching limits for youth ball have arrived, even at Koshien, and the public is now questioning whether a victory-at-all-cost tradition is worth the cost.

In 2019, when Japan's hardest throwing high school pitcher, Roki Sasaki, sat out of a critical game, a nationwide debate erupted.

This past April, Sasaki's pro manager removed him three outs from his second straight perfect game, and it caused barely a ripple. This was the surest sign that fans and players now see baseball as something with a future rather than a tradition to be followed.

By Jim Allen,

By Jim Allen,