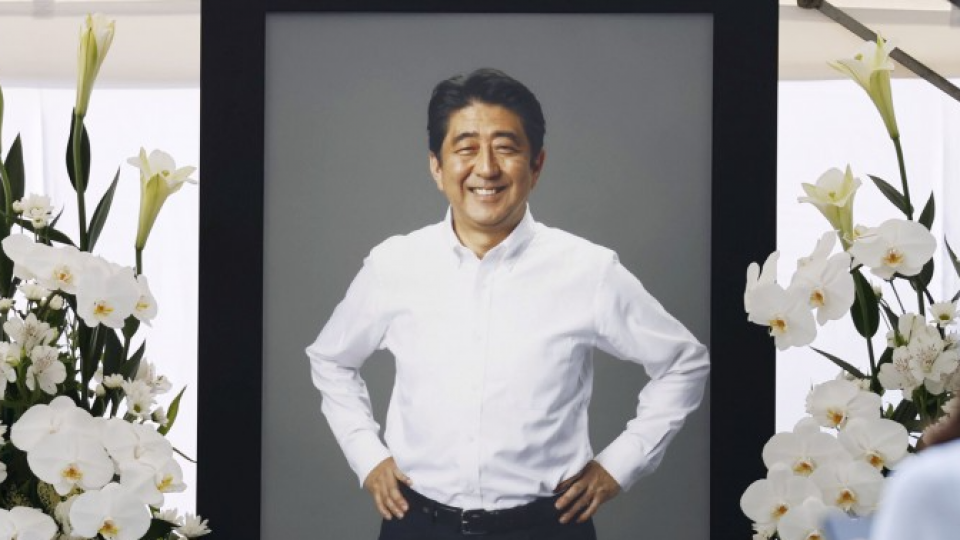

Views held about the influence and contribution made by Shinzo Abe during his lifetime in politics, and especially his more than eight years as prime minister, are strikingly different inside and outside Japan. In some ways this is normal: long-serving prime ministers always tend to create more enemies or critics at home than abroad.

It was exactly the same with Britain's Margaret Thatcher. Yet as with Mrs., later Baroness, Thatcher, with Mr. Abe there is another reason: he was a politician with strong convictions, and as a result was a much more polarizing or controversial figure at home, where people were likelier to agree or disagree with his views, than he was abroad.

If I look at what he achieved during his time in office, it is also the case that his achievements in domestic policy were much less significant, or at least much less noticeable, than his achievements abroad. In foreign and security policy, Mr. Abe and his team of ministers and officials will be counted by historians as having been genuinely transformative.

In domestic policy, especially economic but also social policy, historians will see the Abe era as one that is largely of continuity, with the changes made being incremental rather than radical.

What is also true, however, is that it was in foreign and security policy where Mr. Abe's longevity in office was really able to count. The merits of consistency of personnel and leadership are much clearer in diplomacy and in the slow but important task of building regional institutions and relationships, than they are in domestic affairs.

At home, powerful interest groups often dictate policy or at least they determine how much space there is available for innovation. In foreign policy, there is more room to manoeuver. Or, certainly, there was for a man who with his team had a pretty clear vision.

That vision came in great contrast to the confusion and incoherence of the governments of the Democratic Party of Japan, under three prime ministers inside three years, that preceded Mr. Abe's triumphant return to office in 2012. That spell of DPJ leadership caused doubts in Washington, D.C., about Japan's intentions in East Asia, about how Japan wanted to position itself between China and the U.S., and about what kind of security policy Japan was prepared to develop.

What stands out to an international observer is the clarity of purpose and coherence of implementation that the second Abe administration showed in its foreign policy. This was made evident by the internal reorganization that the Abe government made, creating the National Security Secretariat, and developing a clear and well publicized national security strategy.

It was also shown by the way Mr. Abe at times prioritized international commitments over domestic interests, as when he chose to join the Trans-Pacific Partnership negotiations initiated by the Obama administration and to sacrifice domestic agricultural interests for the purpose.

Even more striking was the way in which Mr. Abe's Japan showed regional leadership when, in 2017, Obama's successor, Donald Trump, withdrew from the TPP, and Japan led the effort to rescue and revive it, under the new name of the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership. To outsiders, this initiative showed that under Mr. Abe Japan had decided to be more forward-looking and even assertive in its foreign policy, rather than passive and somewhat reactive, as was the case in the past.

The result can be seen today in the very outgoing, forward posture being shown by the Kishida administration in the aftermath of Russia's invasion of Ukraine. Japan is no longer keeping its head down and trying to please everybody: it is standing up for clear principles, and taking action alongside the rest of the West.

Compared with all of that, the much-heralded "Abenomics" will, in my view, be seen as having been largely an exercise of salesmanship rather than a period of true policy innovation. The Bank of Japan innovated through its much more aggressive monetary policy, essentially providing direct financing to public spending. But neither fiscal policy nor structural, regulatory reforms went very far beyond previous practice.

Mr. Abe left Japan largely where he found it: as in effect a cheap labor economy with 40 percent of the workforce on short-term and nonregular contracts, declining marriage and birth rates, and chronically depressed household demand.

It is in foreign and security policy that Mr. Abe's legacy really lies, which is why in the aftermath of his untimely and tragic death he has been much more highly praised abroad than at home, where his achievements were fewer and his opinions more controversial.

(Bill Emmott is a writer and consultant best known for his 13 years as editor in chief of The Economist in 1993-2006. He is now chairman of the International Institute for Strategic Studies in London, of the board of Trinity College Dublin's Long Room Hub for Arts & Humanities, and of the Japan Society of the UK. He is currently an Ushioda Fellow of Tokyo College at the University of Tokyo.)

Related coverage:

OPINION: Shinzo Abe, standard-bearer of rule-based order in Asia and beyond

By Bill Emmott,

By Bill Emmott,