With China sticking to its radical "zero-COVID" policy, citizens in Beijing are worried that a window may suddenly pop up on the smartphone app designed for the Communist-led government to collect personal health information.

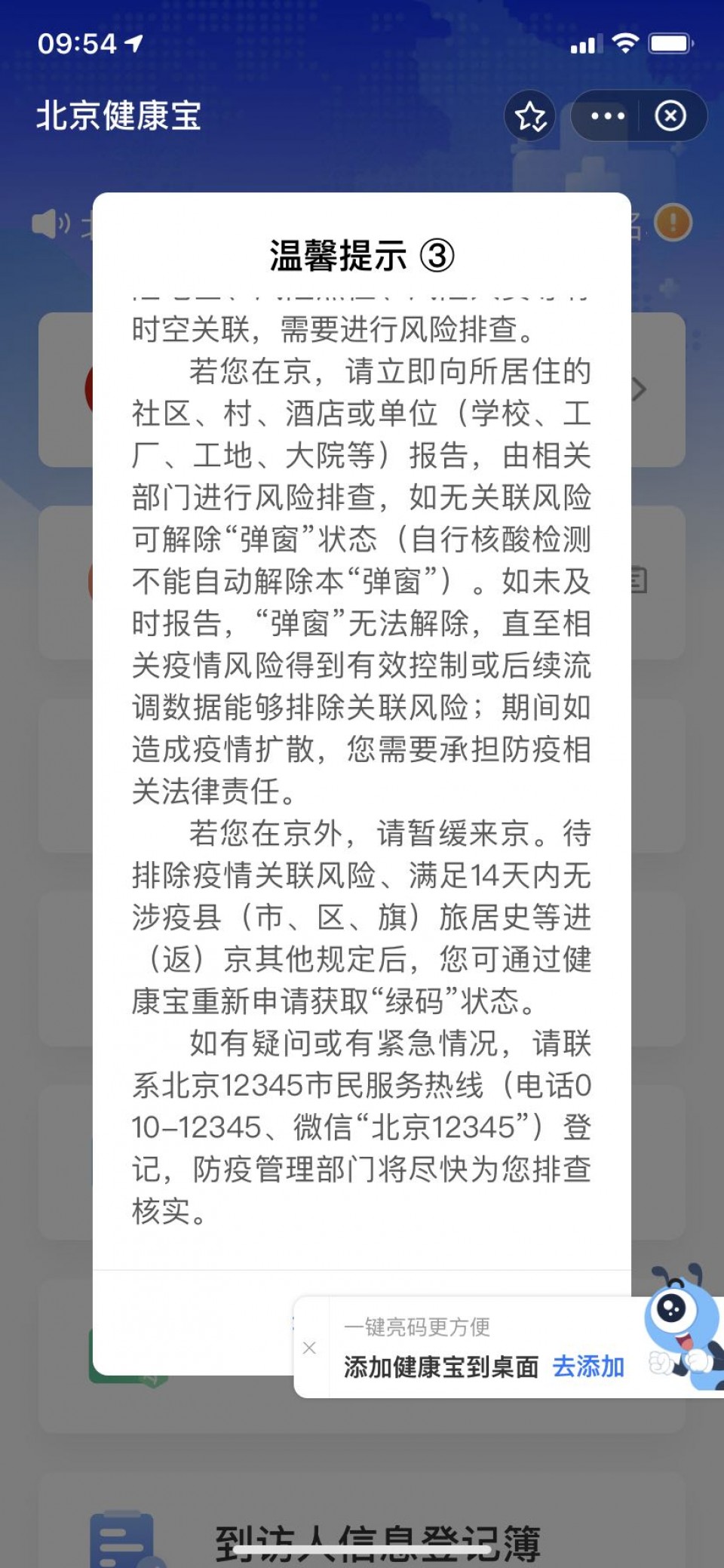

If they see the pop-up window on the app, their "health code," which identifies they are not infected with the novel coronavirus, turns invalid, meaning they are prohibited from entering office buildings, restaurants, supermarkets and any other public spaces.

In the worst-case scenario, they could be forced to quarantine at home for at least seven days until the window, called "tanchuang" in Chinese, disappears, even though they are well. In Beijing, people in quarantine are confined to their home and cannot step outside.

"It's like Russian roulette," said a 42-year-old Chinese woman living in the country's capital, adding, "We've become more unwilling to visit crowded places and even hospitals." Beijing residents mandatorily install the app to show their COVID-19 status.

After the COVID-19 pandemic started to rage in early 2020, China introduced a health code system that can confirm whether a person has a high risk of infection. The system also displays when the person last took a PCR test.

If a green light is shown on their smartphone after they have scanned the QR code positioned in front of almost every facility, they are permitted onto trains and expressways, and into shops and office buildings.

"I try to avoid scanning the QR code as much as possible in order not to get the tanchuang," the woman said.

In recent days, the Chinese government has eased some anti-epidemic regulations, as the more than two-year zero-COVID policy has apparently been taking a heavy toll on business and consumer activities in the world's second-biggest economy.

On Tuesday, China decided to shorten the centralized quarantine period for overseas arrivals and close contacts with virus carriers from 14 days to seven days in consideration of the characteristics of the highly contagious Omicron variant.

But Minoru Yamada, a 38-year-old Japanese man who received the tanchuang warning in Beijing in May, voiced concern that China will tighten its COVID-19 restrictions again if the outbreak re-emerges in the nation with a population of 1.4 billion.

"I don't know why I received the tanchuang because I just divided my time between work and home for the past few months. I negotiated with my residential district, but my family and I were all compelled to be quarantined at home for 14 days," Yamada said.

"We also remain concerned that Beijing might be locked down like Shanghai. We have to keep fighting the fear of a lockdown. We're exhausted," he added.

In Shanghai, China's commercial and financial hub, tough quarantine rules prevented drivers from delivering goods under the two-month lockdown that began on March 28, making it difficult for citizens to obtain adequate supplies of food and daily necessities.

During the lockdown period, two Japanese living in Shanghai died, the Japanese government said, though it has not officially announced the cause of their deaths. A source close to the situation, however, said one of the two committed suicide.

In Beijing, many people try to stock up on food amid mounting speculation about a possible lockdown, as the Chinese capital has conducted mass PCR tests across the city for around two months since late April.

Local media reported in mid-May that a Chinese woman was detained by authorities for allegedly having spread a false rumor that Beijing would soon come under a citywide COVID-19 lockdown.

In fact, the Beijing government effectively sealed the capital for over one month through early June as it required citizens to work from home. It also shut down every school including kindergartens, with many schools providing online lessons for their students.

Most restaurants in Beijing have now resumed normal dining operations, having previously only been allowed to engage in takeaway and delivery services. However, people who have not tested negative within the past 72 hours cannot enter a public place.

Even now, if someone is confirmed to have tested positive for coronavirus, the apartment or residential district where the person lives is abruptly locked down.

Takashi Yamasaki, a 51-year-old man from Japan working in the city, said his company has become reluctant to send staff from Japan to China, given that the strict zero-COVID policy could have an adverse effect on business and mental health.

But there are concerns that the zero-COVID policy is not being implemented properly.

A Chinese man working in Beijing said he has experienced an "air" PCR test, during which the cotton swab did not touch anywhere in his mouth.

A Japanese government source said, "This could happen as local officials don't want infection to be detected in their district. If infection is confirmed, they will be punished."

China has expressed its resolve to continue its zero-COVID policy even following the end of the Beijing Winter Olympics and Paralympics earlier this year.

There are expectations that the ruling Communist Party will enforce COVID-19 regulations until the end of its twice-a-decade congress in the fall, at which President Xi Jinping is set to secure a controversial third term as China's leader.

Xi was quoted by the state-run Xinhua News Agency as saying on Wednesday, "If we make an overall evaluation, our COVID-19 response measures are the most economical and effective."

In mainland China, the number of new daily community infection cases has fallen below 100 in recent weeks, according to the nation's health authorities.

By Tomoyuki Tachikawa,

By Tomoyuki Tachikawa,