On Jan. 16, 2021, I learned that I had tested positive for the novel coronavirus.

My symptoms remained mild, however, and I returned to work the following month as a 33-year-old female reporter in the domestic news department of Kyodo News.

But from my first day back, I suffered from a malaise -- I felt the kind of fatigue one might experience after staying up all night. And I also felt something akin to the flush of a high fever, although my temperature was normal.

Simply standing was difficult. I frequently slumped onto the office sofa. Since the feeling would pass if I rested a bit, I thought I would eventually get better. But to this day, more than a year since my infection, I continue to struggle with the aftereffects of COVID-19.

By the end of April last year, my fatigue had intensified to the point where I found it hard to get out of bed. Suspecting I'd been re-infected with the virus, I underwent a PCR test, but the result was negative. I had intense pain in my upper arms, among other areas of my body, with discomfort so bad I could not sit up.

According to physician Koichi Hirahata of the Hirahata Clinic in Tokyo, who is familiar with the aftereffects of COVID-19, patients with so-called long COVID symptoms can in some cases end up bedridden, with their illness evolving into what is commonly known as chronic fatigue syndrome.

Discussing my symptoms with him, Hirahata advised me to take a leave of absence from work. Prescribing strict bed rest, he said that if I didn't rest up, I would indeed end up bedridden.

Of 1,832 job-holders who visited the same clinic, 736 had taken work leave (as of Dec. 18, 2021). Including those who had shortened their working hours, two-thirds of patients had seen their jobs impacted by the long-term effects of COVID-19.

Afterward, although I spent my days doing nothing in particular, my condition gradually worsened. Even something as simple as peeling a grapefruit or holding up a blow dryer could trigger a deterioration.

In extreme cases, I would feel as if I had some intense inflammation stirring inside my body, and I would find it almost impossible to breathe.

Once while writhing in pain on the floor, an electrical cord came into view, and I had an impulse I'd never felt before -- perhaps it might be easier to die than continue this way.

Moreover, things that I would usually never think twice about, such as the sound of the kitchen fan or the faint ambient light from outside leaking through a window, began to bother me, and I could not sleep. Sensory overload is a symptom of CFS.

Becoming intensely anxious that I might eventually become bedridden, I cryingly asked my mother, "Will I ever be cured?"

Struggling with what seemed to be the interminable extreme pain I experienced every day from the aftereffects of COVID-19, I came under severe mental strain. But after several months, I began to see a glimmer of hope.

This came from the treatment of a not widely known condition called chronic epipharyngitis, seen in some people with CFS. The condition specifically refers to swelling in the back of the nose and throat.

According to Osamu Hotta of the Japanese Focal Inflammation-related Disease Research Group, many patients with COVID-19 aftereffects have acute, chronic epipharyngitis.

It is thought that chronic inflammation occurring at the boundary between the nose and throat due to viral infection causes blood congestion, triggering a decline of brain function and autonomic neuropathy in which the nerves that control involuntary bodily functions are damaged.

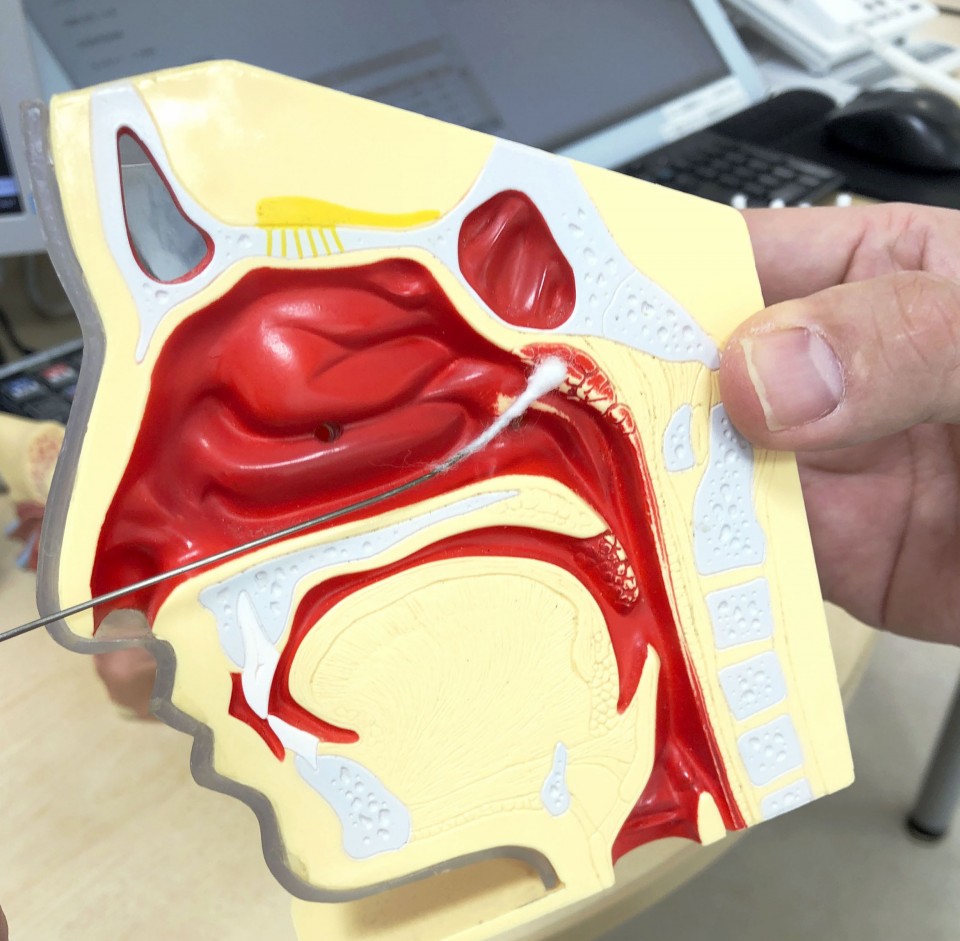

The treatment calls for poking a cotton swab soaked in a zinc chloride solution into the nose and throat and rubbing the affected area to eliminate congestion by the action of zinc destroying bacteria, thus relieving inflammation.

I received this treatment, known as Epipharyngeal Abrasive Therapy, over 70 times.

When I initially began the visits, I had intense pain as if I had been struck on the back of the head with a blunt instrument. But after the treatments, though only for a short while, my head would clear. More than anything, I was happy for a glimpse of improvement, and I continued the treatments.

By the end of August last year, my problems in daily life had for all intents and purposes disappeared. As I aimed for a full return to work, I got involved in reporting on a story that took several hours of coverage over two days.

Immediately afterward, my condition deteriorated once again. I fell into a state of self-loathing at the prospect of not being able to work for even a short period. My body, I felt, was continuing to betray me.

Again, I took care to get enough rest and finally returned to the company at the end of November. Hirahata had advised that, as much as circumstances allowed, I should return "in a way that would not involve stress." So with the understanding of my company, I began teleworking. Nevertheless, I had a relapse of fatigue from my first day back at work.

Unlike before, I recovered when I rested for a while. But I still feel to this day that I walk a tightrope, aware that my condition could suddenly deteriorate. I ask myself, will the day come when I can regain my former self?

At the end of last year, I visited the National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry in Tokyo, which has an outpatient clinic for those suffering from long COVID symptoms, to discuss my condition.

Wakiro Sato, the doctor who examined me, said, "There are reports that fewer people complain of symptoms as time passes after (COVID) infection, but for other people, recovery is unsatisfactory. It is unknown to what extent you will recover."

As elsewhere, the Omicron variant of the virus is spreading in Japan. Although experts point out the comparatively low risk of severe symptoms compared with other strains of the virus, I hope people -- especially the young -- will not let their guard down.

Even if one's symptoms are not so bad, many young people like myself suffer from the long-term effects of COVID-19. My hope is to impart the gravity of this through my experience.

Related coverage:

FEATURE: Reduced brain function, immune disorder a possibility of "long COVID"

Japan considering easing nonresident foreigner entry ban in March

Japan's COVID-19 death toll tops 20,000 amid Omicron spread

By Sayako Akita,

By Sayako Akita,