Mio Shinkawa, a sophomore who attends a private university in Tokyo, took all her classes virtually in her first year and failed to make a single new friend.

When her second year started in April, she finally began in-person classes once a week. Nevertheless, her experience so far has made her question whether she feels like a college student at all.

"I think to myself, 'Who the heck am I?" Mio, 20, said in a recent interview with Kyodo News.

Every day, she repeats the "task" of taking her lessons through a computer screen, completing the many assignments presented to her online.

And while she had been looking forward to joining the university's drama club, the requirement to take PCR tests for COVID-19 every month put her off because of the cost as well as her fear she might "cause trouble" to others in the club if she ever tested positive.

Mio, who lives with her parents, had imagined an altogether different campus life of eating with her friends in the school cafeteria and going on trips together.

"I just want to live the ordinary life of a college student," she said.

When a friend from high school who attends another university gradually begun to take more in-person lessons, Mio dreaded hearing her tales of campus life and became estranged from her.

She has lost her appetite due to the stress and dropped 5 kilograms in weight.

Seeing her younger sister, a third-year high school student, head to school each day also gives rise to complicated feelings, Mio says.

"Why is it that only college students are (in this position)? I am no longer a high school student, but I don't feel like a college student now either," she said.

Kotono Aihara, a 19-year-old who enrolled at an art university in Tokyo last year, also took all of her classes online for a year. Like Mio, she too started in-person lessons in April, albeit full time, but when the government declared another state of emergency, she returned to a cloistered life of only virtual lessons.

Kotono feels guilty because she does not think the studying she does is worth the 2 million yen ($18,200) her parents shell out in tuition fees. Like Mio, she says finding friends in a life of isolation has been trying.

"There are college students, (people) I have got to know through social media, but I've never met them (in person), and don't know their names or faces," Konoto said.

Yuika Morioka, a 19-year-old sophomore studying education at a private university in Tokyo, says she had no choice but to look for fulfillment off-campus because of the isolation from attending virtual classes.

Although students are given time to converse during virtual lessons, she says it is difficult to interpret each other's facial expressions through the screen, and that participants often fall silent with nothing to say in their chats.

Despite being taught that "nonverbal communication" is important in educational settings, she says it is a skill that she herself is not learning.

She worries that in the future, people such as herself might come to be seen as members of a "corona generation" inept at communicating face-to-face in front of real people due to their long periods of isolation.

There were times when Yuika would not leave her home for close to a week. Sitting in front of her computer screen for long stretches, she would be overcome with a tremendous sense of loneliness -- even the illusion that "perhaps I am the only person in the world."

Yuika's turning point came in April. She was invited through social media to participate in a local community group of young people striving to deepen interactions and help the many others who find themselves in similar straits dealing with loneliness or isolation under the pandemic.

Local residents organize the events so participants can gain a sense of worth, she says.

"Honestly, I wanted to learn this type of practical knowledge at my university," said Yuika.

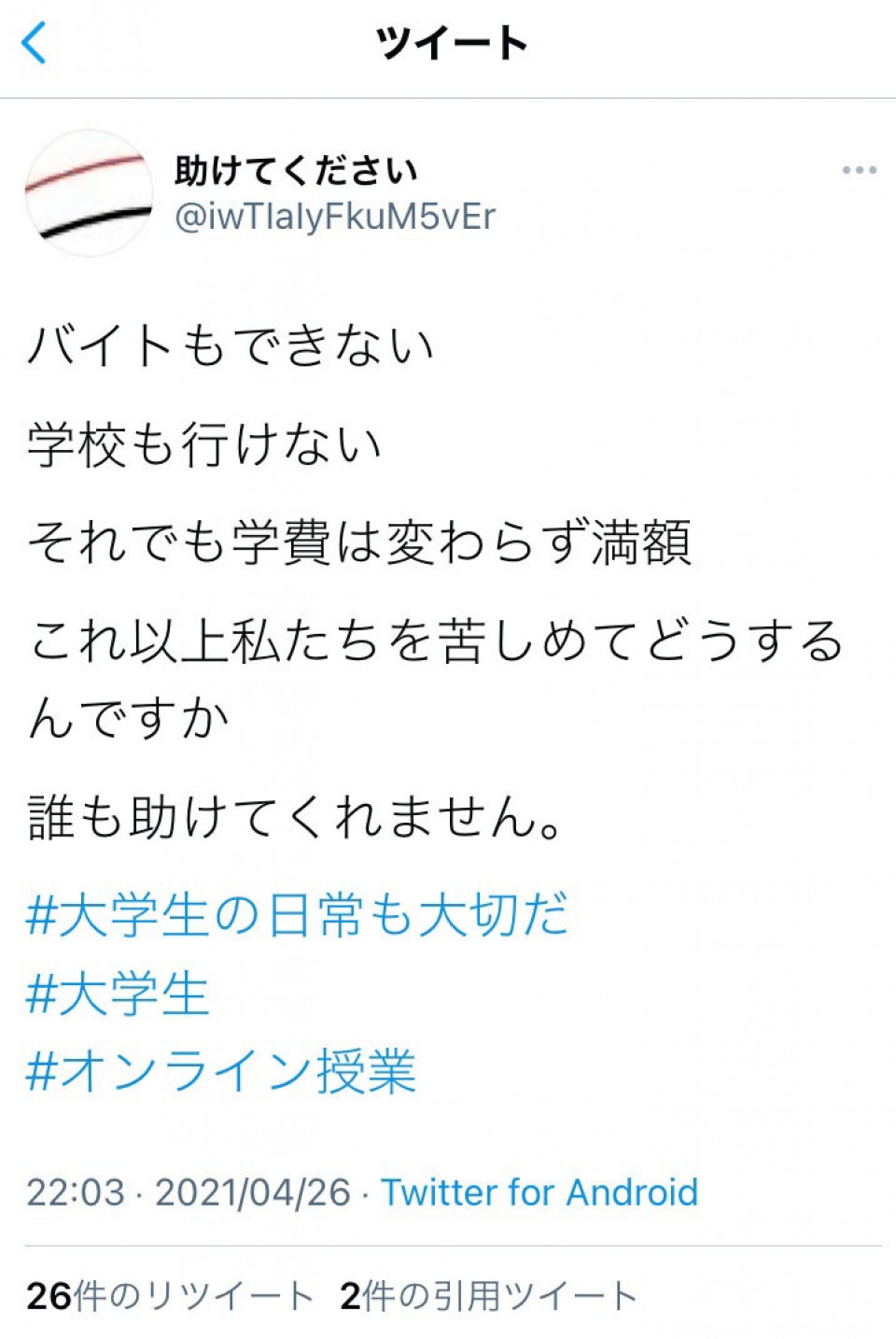

There has been a deluge of posts on Japanese social media with a hashtag that loosely translates as "the everyday lives of college students also matter," calling for the full-scale restart of in-person university lectures.

Some of the posts read, "What was the purpose of getting into college anyway?" and "Don't make me suffer anymore more than this."

Recent data has shown the havoc the pandemic is wreaking on the mental health of young people.

A nationwide survey of 1,744 people, mainly college students, conducted in March by the education ministry found that about a third of respondents were concerned about making friends in school or college -- most saying they are unable to make new friends or interact with the friends they already have to the degree they had hoped.

Another survey conducted from May to June last year by Akita University found that more than 10 percent of respondents had moderate or more serious symptoms of depression.

A Tokyo nonprofit, which conducts a 24-hour hotline chat, has around 700 volunteers who respond to 670 consultations from people on average per day, 80 percent of whom are 29 and younger.

Koki Ozora, 22, a senior at Keio University and the group's chief director, says the number of people seeking counsel amid the pandemic is "overflowing like a muddy stream."

"We are under tremendous strain," Ozora said, adding, "It will be necessary to expand our consultation operations."

The consultations vary with people concerned about everything from an inability to make friends to being financially strapped after losing their part-time jobs.

In 2020, the number of suicides increased to more than 20,000 -- the first time in 11 years it rose from the previous year, an indication that the pandemic is pushing people to the brink. The remarkably high number of women and young people among suicide victims added to the sense of crisis.

The Japanese government, in response, in February appointed a "minister of loneliness" to help alleviate alienation in society under the pandemic. In March, it announced a plan to allocate 6 billion yen in financial assistance to nonprofits for working on suicide prevention.

"Loneliness must be seen as a problem for society as a whole, not for individuals. How many people are driven into loneliness? It's necessary to grasp the actual situation and have the government work on countermeasures," Ozora said.

By Manami Misono,

By Manami Misono,