The Japanese government hastily withdrew plans to pressure restaurants via lenders and liquor suppliers not to serve alcohol during states of emergency over the coronavirus, but the controversy shows how it has been relying on impromptu steps in the absence of an adequate legal framework for addressing pandemics, experts say.

The blunder by Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga's administration also exposed the limitations to a request-based approach to getting businesses to restrict their operations a year and a half into the health crisis, they said.

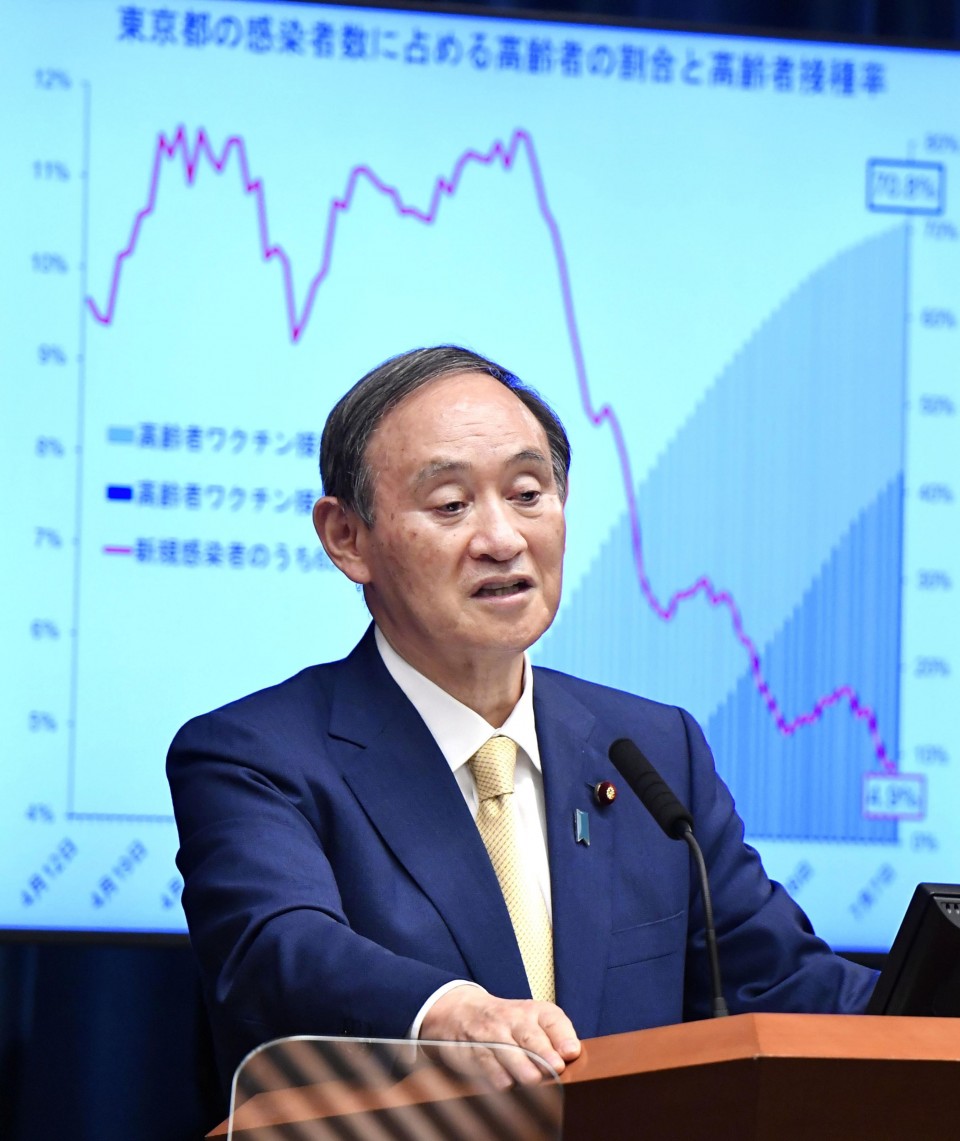

Yasutoshi Nishimura, the minister in charge of Japan's coronavirus response, set off the controversy at a press conference July 8, the day the government decided to place Tokyo under its fourth COVID-19 state of emergency, effective from July 12 through Aug. 22.

With signs of a drop in the number of restaurants willing to follow the government's calls for virus-related restrictions, he appeared to ask banks to play enforcer.

"By sharing information with financial institutions, we'll ask them to urge unwilling establishments to comply with" measures, Nishimura said.

Under the virus emergency now covering the capital and the southern island prefecture of Okinawa, restaurants and bars are ostensibly prohibited from serving alcohol and required to close their doors by 8 p.m.

"I think the administration assumed that the tougher the steps it took against restaurants and bars, the more the media and public opinion would welcome them as thorough virus countermeasures," said Yasuyuki Iida, an associate professor at Meiji University.

Instead, members of both ruling and opposition parties were quick to criticize the proposal and the government was forced to retract the plan the following day.

In the Tokyo entertainment district of Shibuya, a wine bar owner who had already decided to keep serving alcohol under the latest state of emergency said Nishimura's remarks had likely just put even more establishments off complying with the alcohol ban as they seek to stay afloat.

"I can get monetary compensation of only 40 percent of sales, which is too little to cover fixed costs such as rent," said the owner, 50, who spoke on condition of anonymity. "I know restaurants and bars should cooperate (with the government), but the compensation is totally unfair."

Nishimura's remark "really rubbed us the wrong way and proved that they can't understand how we feel," the owner added, saying that he had heard from others in the same business that the comment had prompted them to decide not to comply with government requests any longer.

Iida, an expert in economic policy, said that if banks did refuse loans to businesses in line with what Nishimura appeared to be proposing, it could be regarded as an abuse of a dominant bargaining position and thus violate the anti-monopoly law. Such a request by the government could also threaten the freedom of business activities, he added.

Banks likely shied away from the idea of taking any such action, so the measure was never going to be effective, Iida said.

But "Suga's administration probably gave priority to being portrayed as being strict in dealing with the virus, rather than being effective. It was erratic policymaking and just political grandstanding."

At the same time as his call on banks, Nishimura also outlined another plan to ask beverage wholesalers to stop supplying liquor to eateries during the virus emergency, and at first, the government stood by it.

But in the end, protests from an industry group of retail liquor shops and concerns over the impact of the uproar in Suga's Liberal Democratic Party ahead of a general election that must be held by November led to the request being abandoned on July 13.

Mitsuru Fukuda, a professor at Nihon University College of Risk Management, said that legal frameworks for crisis response should be hammered out "in ordinary times after thorough discussion," slamming both measures proposed by Nishimura for lacking a legal basis.

"Making laws in the midst of a crisis could be really dangerous because they tend to be crafted under a logic justifying infringing private and human rights," said Fukuda, an expert on risk management, saying that the government appeared to be in the grip of that kind of mindset when Nishimura made his proposals.

Since its first virus emergency last spring that disrupted many social and economic activities, Japan has refrained from going into the kind of hard lockdown some major cities around the world have imposed and has largely relied on the voluntary cooperation of the public and businesses, with steps mainly focused on restricting the operations of eateries.

But with each virus emergency, more such establishments are flouting the requests.

"Instead of putting efforts into crisis management such as securing enough beds for (coronavirus) patients, what the government has done so far is all about requiring people to have patience, so it's natural that the government loses peoples' trust," said Fukuda.

"Request-based measures work well when the government has gained public confidence, but the emergency has been repeated as many as four times. The latest development has exposed the limits of such an approach," he added.

By Keita Nakamura,

By Keita Nakamura,