Foreign workers in Japan, who are essential to the aging country, have been one of the demographic groups most affected by the economic downturn due to the coronavirus pandemic.

While many such workers were fired or furloughed as a result of the economic fallout, some are striving to empower themselves and improve the situation surrounding their employment.

Among them is a Filipino woman living in the central Japan prefecture of Aichi, which has the biggest Filipino population in the country - 39,339 as of late 2019, according to the Justice Ministry, many of whom are employed in the manufacturing sector.

"I'd like to create a good working environment for foreigners," said the woman, who goes by the pseudonym Maria Santos as she worries her union role may hinder her search for a job.

Santos formed a labor union for workers from outside Japan in Aichi last June along with 15 other Filipinos after they were laid off or their fixed-term contracts not renewed in the wake of the pandemic.

Her union named Aichi Migrants Workers aims to help foreign workers and is the first local community-based union for non-Japanese laborers in Aichi.

With the help of a local union named Union Aichi, AMW holds monthly study sessions on Japan's labor systems and laws and as of early March has 24 members from the Philippines.

Related coverage:

Japan's Filipino community puts down roots, moves past hostess origins

FEATURE: Remote Japan island "getting energy" from Vietnamese students

"We, as foreigners, want to help each other by learning the employment system here," said the 56-year-old Santos, who holds long-term resident status in Japan, having arrived here in 1988.

Santos, who has worked several different jobs while raising her children, first started thinking about setting up a labor union two years ago, she said.

But in March of last year, she lost her job at a plant that assembles automobile parts after her contract as a dispatched temporary worker was not renewed.

Realizing that she was not the only non-Japanese worker to have lost their job was her motivation, she said, in forming the union.

Unsure about unemployment benefits and having been paid less than was stipulated in her contract, Santos said the union holds sessions to teach its members about the labor system.

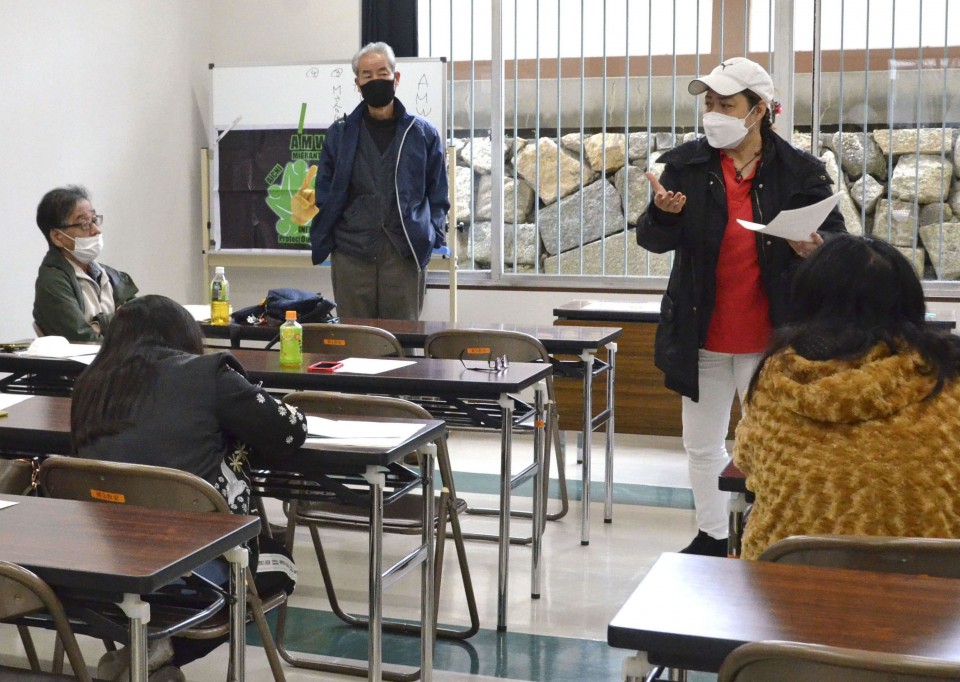

In mid-February, Santos and several other members of the AMW as well as some from Union Aichi gathered for such a meeting at a rental room in Nagoya.

An official of Union Aichi talked about the mechanism of labor unions and workers' rights in Japanese and Santos interpreted the explanation into Tagalog and English.

Santos said she hopes to increase the membership of AMW by attracting not only Filipino workers but also those from other overseas countries through the learning sessions and exchange events.

"A lot of foreign workers (in Aichi) have been employed for a limited term and are used as fluid labor force," often being placed in vulnerable positions, said Hirokazu Mori, secretary general of Union Aichi.

"If they form a labor union, the union members can protest to employers on problems such as layoffs without a rational reason."

Companies cannot refuse requests of negotiation from labor unions under labor standard law, Mori said, noting rights such as obtaining paid holidays, which are often not given to foreign workers here, can be restored through the negotiations.

According to a survey of the labor ministry, 93,354 people have lost their jobs due to the coronavirus pandemic as of March 5, with the manufacturing industry suffering the most with 20,536 people being laid off.

While a breakdown by nationality is not available in the data, it is speculated a large number of foreign workers are included in the figure, with Mori saying his union has heard from a number of non-Japanese workers in Aichi who have lost their job in the past year.