Hundreds of works of art created by Japanese prisoners of war and civilian internees detained in Australia and New Zealand during World War II have been studied for the very first time by academics, having been "entirely ignored" by scholars for decades.

In their article, published in the Australian and New Zealand Journal of Art, co-authors Richard Bullen from the University of Canterbury and Tets Kimura of Flinders University said the works complicate the commonly accepted narrative of Japanese people during wartime and provide further insight into the "isolating and traumatic experience of internment."

Bullen, 52, told Kyodo News that unlike internment camps in the United States, the history of wartime detention in Australia and New Zealand is largely unknown.

Despite having devoted his career to studying Japanese art in New Zealand, Bullen said he had no idea the works existed until very recently.

"It's quite extraordinary," the associate professor of art history and theory said in a phone interview. "The artworks that were produced at the camps...have been, until this point, entirely ignored."

Throughout the war, roughly 5,000 Japanese or part-Japanese POWs and civilians were interned at eight locations across Australia and New Zealand.

The authors say the style and medium of the artworks, which include paintings, sculptures and game pieces for mahjong and traditional Japanese "hanafuda" playing cards, varied greatly by location.

Artwork from camps in South Australia, where native hardwood was available, included intricately carved marquetry boxes and large three-dimensional wooden sculptures, while pieces from New Zealand were often painted onto wooden offcuts from camp construction materials.

Artists also used easily attainable medicines instead of paints to color their works.

"Some of the most beautiful pieces are the games like hanafuda cards and mahjong sets," Bullen said, noting that some works appear to have been created by individuals with artistic training.

"Some were made for exchange (with guards) for tobacco or camp currency, but a lot were made for playing in the camp."

In addition to trading art with guards, the authors found prisoners also gifted works to local farmers and nurses who had shown them particular kindness.

However, despite the artworks facilitating relationships across the wartime divide, Bullen said the situation at the camps should not be misinterpreted.

"It's easy to look at the camp and say 'Oh look at all the beautiful artworks and everyone got on so well because they were exchanging (art) with the guards," because that's clearly (incorrect)," he said, noting the significant power dynamic between prisoners and guards.

"The prisoners were making items which would have taken hours and hours of work for a little bit of tobacco or a small amount of money...It wasn't a happy situation for the prisoners. None of them wanted to be there."

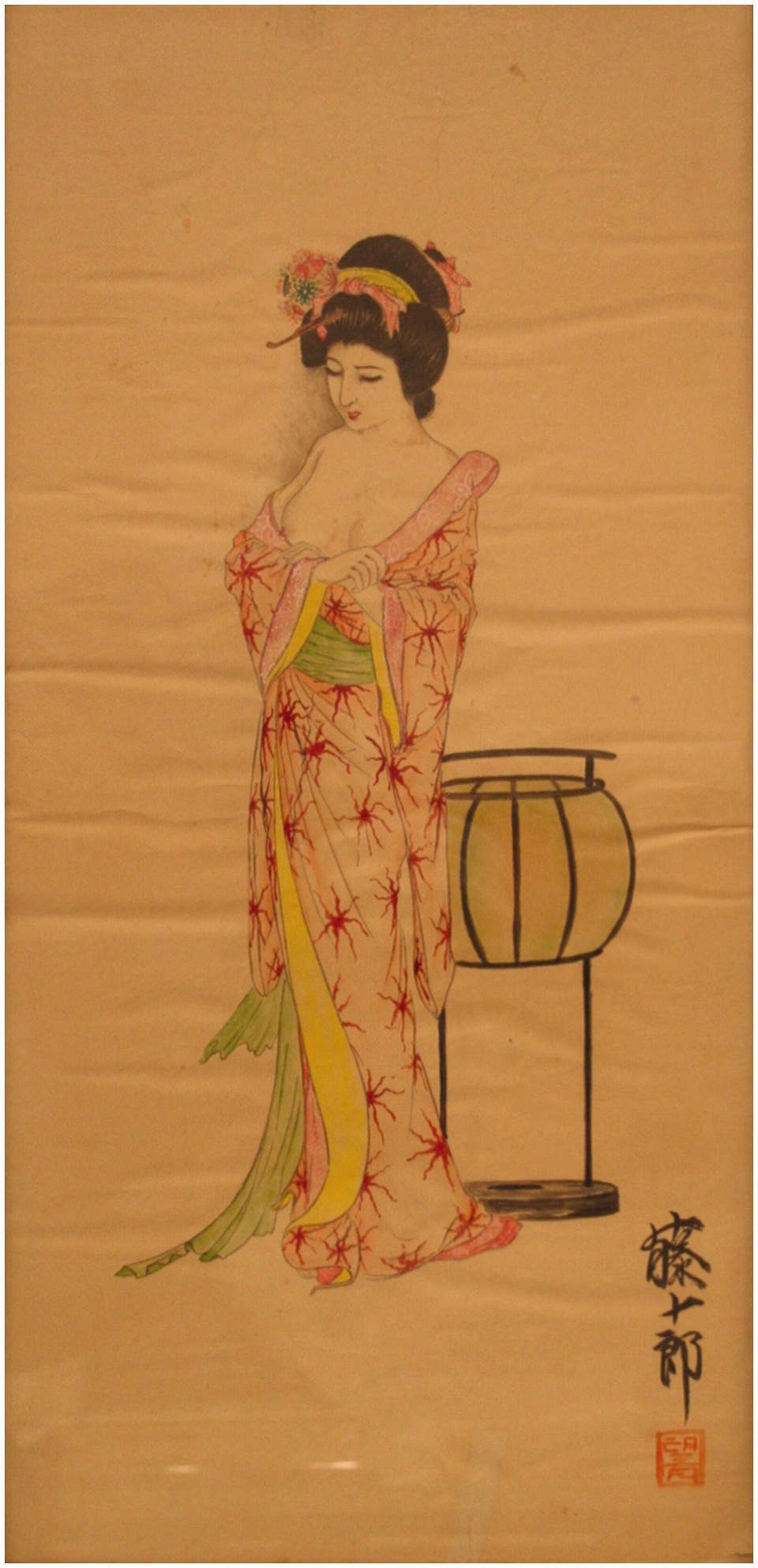

Bullen said in addition to feelings of nostalgia or homesickness for Japan displayed through depictions of women dressed in kimono, landscapes of Mt. Fuji, there is also a sense of nationalism and militarism seen through images of Japanese castles and the "hinomaru" wartime flag also featuring heavily in works.

"There's an underlying nationalism there, perhaps a sense of resistance to the experience they were having, and I don't think that was ever picked up by the guards," Bullen said.

Unlike Japanese prisoners, the authors said works by civilian internees did not depict the same feelings of nationalism. Instead, some civilian pieces are reminiscent of works by European artists.

"Prisoners of war were either Japanese or from the Japanese empire, so Taiwanese or Korean, so their experience and who they were was quite different from a second-generation Australian whose father happened to be ethnic Japanese," Bullen said.

"They're different people (and) we think that's reflected in the kind of art they made."

Following the war, prisoners and many civilians were repatriated to Japan, causing a decades-long hiatus of Japanese art produced in either Australia or New Zealand.

As the authors note, "Ironically, the darkest period of Japanese history in Australasia is the region's richest period of Japanese art."

Related coverage:

Japanese gallery campaigns to share iconic A-bomb paintings worldwide

Nagasaki asks Japan gov't to push nuke ban amid leadership vacuum

By Anna Watanabe,

By Anna Watanabe,