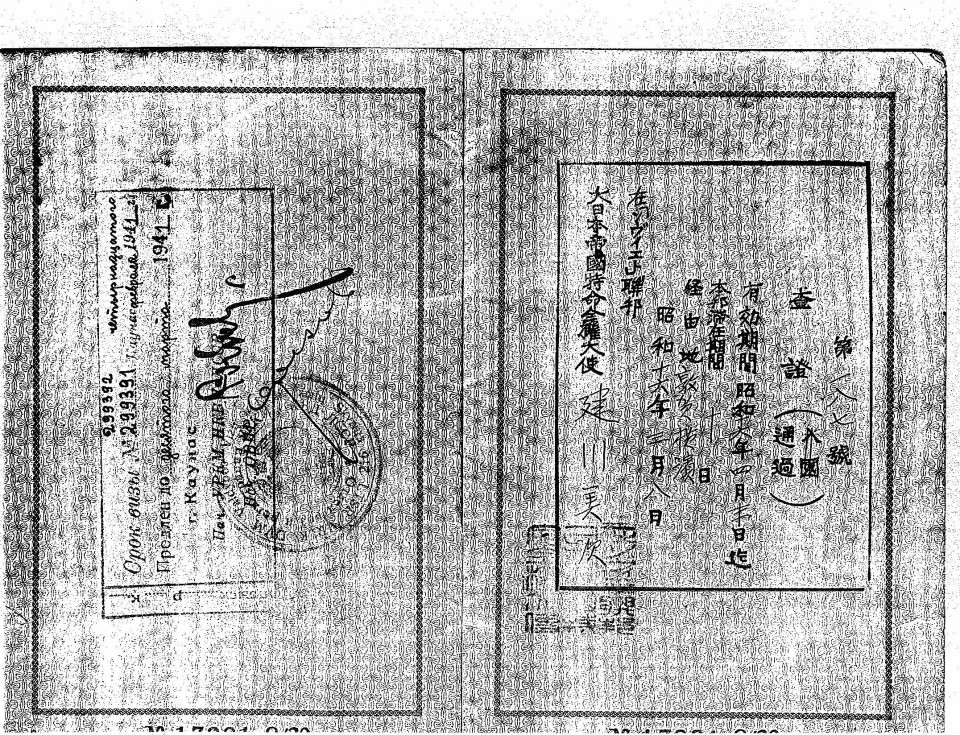

A photocopy of a transit visa issued by the then Japanese envoy to the Soviet Union to help a Jewish refugee flee from Nazi Germany during World War II has been preserved in the hands of her relatives, the family said.

While it is already known that Ambassador Yoshitsugu Tatekawa issued travel documents for Jewish refugees, it is very rare to confirm that he also issued visas for them.

The visa was issued for 17-year-old Rischel Kotler on March 8, 1941 at the Japanese Embassy in Moscow.

Since the Japanese Foreign Ministry had banned visa issuance in the Soviet Union a day earlier, Tatekawa, who was thought to be sympathetic toward Jewish refugees, is likely to have decided to grant the visa on humanitarian grounds.

Given the ministry's ban, Kotler's visa is also highly likely to have been the last Tatekawa issued to Jewish refugees.

According to Kotler's relatives citing her account and relevant documents, she visited the Japanese embassy on the night of March 8, when many other Jewish refugees were gathered outside. Although the other refugees were not permitted entry, a security guard let her in when she said in English that she had an appointment.

In the embassy building, Kotler met with a man wearing what she described as "silky kimono-like clothes." After she told him that she wished travel to Japan, the man pondered for a considerable time and then signed and issued a visa.

Travelling through several locations such as Tsuruga, Fukui Prefecture, Kobe, Hyogo Prefecture and the Chinese city of Shanghai, Kotler visited the United States in 1947 and later settled in the country.

Aaron Kotler, the youngest son of Kotler, told Kyodo News that the security guard probably allowed her to enter the Japanese embassy thinking she was not a refugee.

"She talked about the story hundreds of times," the 56-year-old man said, adding, "She was always very grateful to Tatekawa."

"Without the visa she had no chance of leaving the Soviet Union. Both of her parents were killed by Nazis. At that time no country allowed Jews, including the United States," he said.

Another wartime Japanese diplomat, Chiune Sugihara, is better known for helping Jewish people flee Nazi-occupied Europe and the Holocaust, being credited with issuing thousands of travel documents while serving as acting consul to Lithuania.

Saburo Nei, then acting consul-general in Vladivostok in the then Soviet Union, was also recently found to have signed transit visas issued by Sugihara.

The report on Nei's involvement prompted Aaron Kotler to contact Japanese freelance writer Akira Kitade, who has written a book on Japanese officials who supported Sugihara in his efforts to help Jewish refugees flee from Nazi persecution.

Kitade helped shed light on the role Tatekawa played in helping Jewish refugees.

Along with her husband and her father-in-law, Kotler helped to establish a yeshiva for orthodox Jews in Lakewood, New Jersey. Kotler died in 2015 at age of 92.

"Sugihara and Nei are now famous. But Tatekawa should be honored too. He is the third great rescuer of Jews during the Holocaust," Kotler's son said.

"The story of Sugihara has been told. The story of Nei is now being told. The story of Tatekawa should be told too. I think it is very important to recognize the people, particularly the government officials who make good moral choices in a tough time."

Aaron Kotler is now president of the Beth Medrash Govoha, a yeshiva in Lakewood. The town has thrived as a college town and, as a hub of Orthodox Judaism, has one of the highest percentages of Jewish residents among U.S. municipalities.

Tatekawa was the saver of his mother's life and should be credited for his deed along with Sugiura and Nei, Aaron Kotler said, adding, "No visa, no town."

By Yosuke Watanabe,

By Yosuke Watanabe,