As the effects of the novel coronavirus pandemic ripple across Japan, foreign asylum seekers are among the hardest hit, seeing the support available to them curtailed just as times get tougher during a process that can take years and rarely results in success.

Japan is one of the major donors to the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees, but has been criticized by the world refugee agency for its poor track record of recognizing those who have fled to its shores, with less than 1 percent of applications accepted.

The Japan Association for Refugees, based in Tokyo, was founded in 1999 to assist asylum seekers and lobby the government for a more generous refugee policy. As well as assisting with applications, shelter, food and job searches, JAR officials visit detention centers for those applicants who are taken into custody by immigration authorities and offer individual counsel.

Around 60 percent of the some 600 people each year who request JAR's assistance are from Africa, spokeswoman Kazuko Fushimi said. Unlike Asian refugees who can "plug into" ethnic communities already in Japan, African asylum seekers prefer to rely on NGOs, fearing exposure to compatriots may lead to reprisals from home governments against loved ones back home.

"With lives in danger, refugees are not in any position to choose which country they want to flee to," Fushimi said. They generally go to the country that gives them visas first, despite unfamiliarity with the language and culture.

Around 15 to 20 refugees visited JAR's office daily before the pandemic, but the outbreak forced it to change how it operates.

"What is central to our action is that we cannot infect refugees with the virus. We are determined to prevent that," Board Chair Eri Ishikawa said.

Although the government in late May lifted the nationwide state of emergency it implemented to slow the spread of COVID-19, Ishikawa said they will revert to normal operations only "when (we) feel things have gotten better."

The NGO has opened its doors twice a week instead of four, implemented strict sanitation, reduced the number of staff at the office and introduced telework.

Calls and emails have become the norm, although many refugees can only use public WiFi, made a more difficult task when public spaces were closed during Tokyo's stay-at-home requests.

For those unable to get in touch, JAR has a room for them to speak online to staff members or interpreters working from home. Around 150 people visited the office from early April to early June, Ishikawa said.

"A large part of helping is meeting face-to-face, so we do feel communicating remotely is difficult," including emotionally, according to Fushimi. "Their expressions when they come in the door, their clothes, or what they are holding, a sigh, each is an important element to figure out their situation."

It takes an average of three years for a successful applicant to be recognized as a refugee, although it has sometimes taken as long as 10 years through multiple appeals, Fushimi said. Applicants who had legal status at the time of their asylum application can apply for work permits after eight months, in practice, she said.

But those on provisional release from detention are given no residency and have no work permit or national health insurance. Those in detention centers, meanwhile, are stuck without knowing when they can get out as Japan has no limit on the length of detention.

The association has found shelters for more than 15 homeless refugees since March, more than during the same period last year as they were mindful that recent arrivals with nowhere to stay have a high risk of catching the virus, Fushimi said.

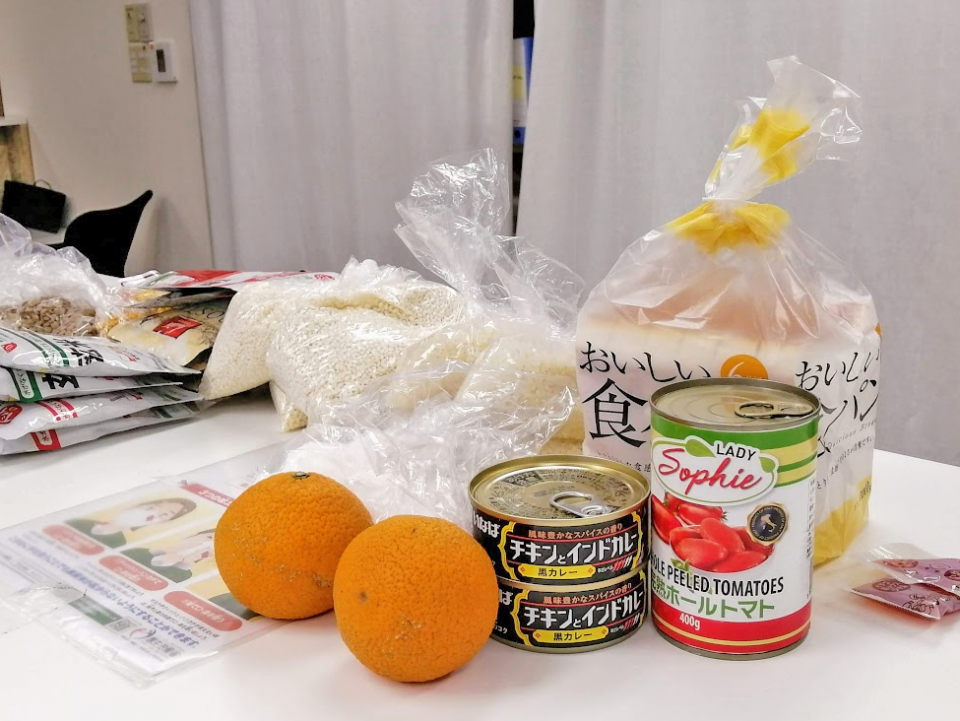

Multilingual information related to COVID-19 went up on its website, including sanitation instructions and government policies; food packages were sent instead of being picked up.

The association, meanwhile, has received an increasing number of calls from asylum applicants with work permits who have lost their jobs. Part-time workers and contractors, particularly in the hotel and retail businesses, speak of hours cut or jobs temporarily suspended.

While this is a pain shared across Japan, an additional difficulty for refugees is their inability to transfer as easily, if at all, to other job sectors, due to their limited language ability.

For those on provisional release, who lack work permits, the situation is direr. The money they brought to Japan evaporates quickly, according to Ishikawa.

Chie Komai, an immigration lawyer at Milestone Law Office in Tokyo, noted how "emotionally painful" it is for refugee applicants to be unable to support their families.

Detained asylum seekers, meanwhile, including those with Japanese spouses and children, feel trapped and helpless, not knowing when they will be permitted to leave, she said.

"Asylum seekers without work permits have a terrible time," said one refugee, who asked not to be named. "They already work secretively for low-pay, and when the coronavirus hit, there were stories about farms and small businesses in rural areas where they worked going bankrupt, leaving them even more destitute."

Mindful of the dire economic circumstances faced by many asylum applicants, JAR has called for the 100,000 yen cash handouts that the central government is providing to citizens and foreign residents to boost the economy to be extended to those on provisional release, too, according to Ishikawa.

The pandemic has also affected JAR's advocacy, including forcing cancelations of events hosted by it or others. The cancelation of some charity sports events planned for March lost JAR more than 6 million yen ($56,000), Ishikawa said.

As the economic downturn continues, JAR is braced for a "greatly reduced" funding as the individual and company donors will find it difficult to maintain their support, Ishikawa said.

JAR has also received a rash of criticisms for its call for asylum applicants to be eligible for the cash handouts via emails, Twitter posts and online comments, according to Fushimi. But at the same time, it has seen an increase in the number of new individual donors, which Fushimi ascribes to people thinking more deeply about the pandemic's effect on the vulnerable.

"We were very worried (about how the pandemic would affect the funding). But in fact, there is a trend of people who had never supported refugees before who have started thinking how the coronavirus pandemic must be affecting vulnerable people," she said.

Health is naturally a concern for those on provisional release who have no health insurance. Even though PCR tests to detect the virus may be free, further medical checks are expensive for them, says Ishikawa.

Those in detention centers have been particularly vulnerable, confined to their closed, crowded, and close-contact settings -- or the "three Cs" that the Japanese government requests people avoid to stem the spread of the virus.

"My clients in detention centers are terrified of catching the coronavirus. More detainees need to get out," said Komai.

The Immigration Service Agency said it would "pro-actively implement provisional release" in its manual revised to take into account the pandemic and released on May 1, which lawyers and other supporters say has happened.

Nevertheless, those released know they could be re-detained at any time, said Ishikawa.

Describing them as individuals "made to be invisible," she said Japan "needs to change the fact that there are people (like asylum seekers) who don't have safety nets."

"Including those people, making sure that they are not left behind is necessary to protect each and every life, and I think will create a society that is strong against COVID," she added.

In 2019, Japan had 10,375 applicants and granted refugee status to 44 under the Refugee Convention, according to Justice Ministry data. The numbers in 2018 were 10,943 and 42, respectively, and in 2017, 19,629 and 20. These exclude refugees admitted under the country's U.N.-led third-country resettlement program of Myanmar refugees from camps in Malaysia and Thailand and other individuals granted Japanese residence permits on humanitarian grounds.

A report by the ministry in 2019 said "the majority of applicants were from countries that are not facing circumstances creating a large number of refugees or displaced persons," with 62 percent of asylum requests from Sri Lanka, Turkey, Cambodia, Nepal, and Pakistan that year.

But critics say that the government's interpretation of "fear of persecution" is overly restrictive and that its criteria for determining who qualifies as a legitimate refugee are murky.

Related coverage:

U.S. downgrades rating of Japan's efforts against human trafficking

Rohingya activists rebuke Japan envoy over denial of genocide

Peruvian man sues state over assault while detained in Osaka

By Mariko Tamura,

By Mariko Tamura,