Some people will shudder at Hiroki Enno's idea of a "social experiment," yet he believes the project could someday benefit society as a whole.

The 28-year-old CEO of Plasma Inc., a Tokyo-based IT company, is paying participants in exchange for allowing him to film their activities at home -- 24 hours a day.

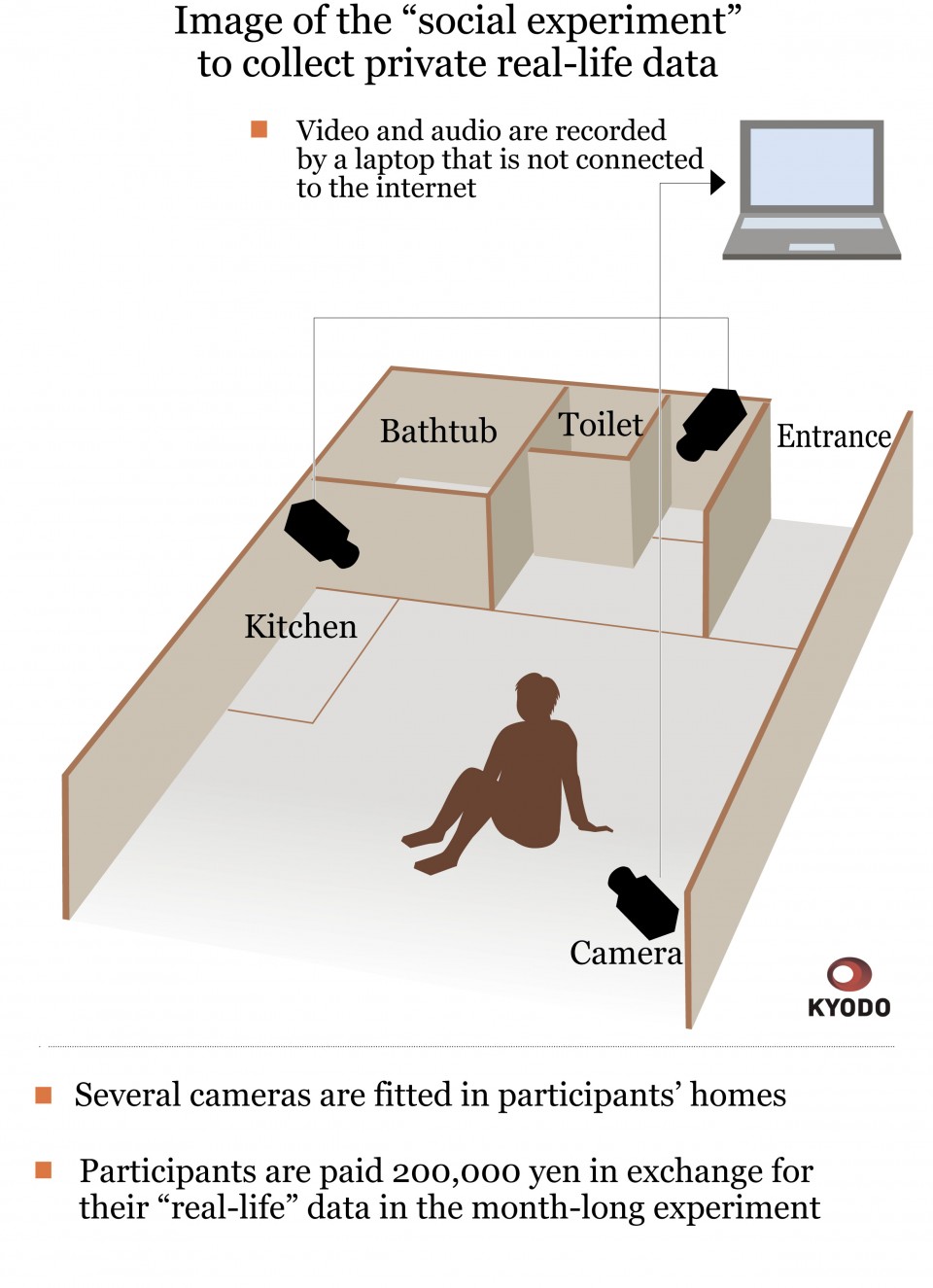

The subjects, whose identities are hidden, each received 200,000 yen ($1,830) at the end of the month-long "Project Exograph." The express purpose of the scheme, which he describes as a "human record of life," is to collect data on consumer behavior to be analyzed by businesses and marketing experts for commercial and other uses.

The catch? The participants had to have most areas of their homes -- even the toilets -- fitted with cameras and now must trust that these videos will never be divulged to the public nor the participants' identities revealed.

Today's YouTubers have created their own "reality" shows on social media, where many exhibitionist so-called influencers amuse or bemuse audiences on the internet.

But Enno might be the first to turn this reality on its head, as the participants in his project are merely living out their everyday existence, not craving the limelight.

Paradoxically, he aims to make the act of filming a person a very private matter, but one that could benefit the wellbeing of humankind in a future age of automation when jobs have become all but obsolete.

"I have a world view based on science fiction. As artificial intelligence (AI) robots develop into the future, there will come a time when people will no longer have to work for a living," Enno said in a recent interview with Kyodo News.

"But the one job people will still be able to do is generate their own life data, which we hope to monetize. This will enable them to afford food, clothing, and shelter."

Two men and two women -- two 24-year-olds and two 29-year-olds -- were selected for the project from some 1,300 applicants. The only area off-limits to cameras during the filming was the bathtub. Laptops, connected to the cameras by cables, also recorded audio.

Plasma chose 24 and 29 as the ages of the four taking part in the experiment since most applicants came from these two pools.

Enno pointed out that big tech companies, notably Google, Amazon, Facebook, and Apple, are already purchasing data that people's digital footprints leave behind.

"Even though these big tech companies are providing information free of charge, people suspect they are secretly taking our data for their own use. So I said, what if I did an experiment in a straightforward fashion and properly compensated people for their private data? Would we still face criticism, and what kind of people would respond? This model is the antithesis of big tech companies."

Enno's objectives are threefold: seek ways to socially and economically utilize offline lifestyle data, demonstrate the value of project despite the intrusive nature of the data collection, and pose questions about the value of sensitive private information in society.

"For example, what time does a woman put on her makeup, and so forth? What does a man in his 20s like to drink after a bath? For the companies trying to develop products to figure out consumer behavior, I plan to provide this search engine. But we will take and stock footage in such a way that it is impossible to identify the person."

One of the four subjects, a woman who lives in a one-room apartment in Tokyo's Suginami Ward, finished the project on the evening of Dec. 23. Kyodo News, accompanied by Enno, was there to talk with her before the cameras were removed.

An "education worker" who turned 30 around the start of the project in November, she explained her reasons for participating while sitting in her tatami-mat room. She heard about the project on a TV talk show and was chosen following a web interview.

"I thought that this type of social endeavor would really be interesting," she said but added that she wouldn't have applied if there had been no money involved. "I don't think I would have done it for 100,000 yen. I think 200,000 yen was the cutoff amount."

Asked what concerned her most about privacy during the filming, the woman said, "When the cameras were installed, I thought this would be tough because there is hardly any place to hide. The only place was the bathtub. As the project progressed, I wasn't nervous, but I never really forgot I was being recorded."

This was especially true when it came to undressing. She asked Enno to contrive a blind spot in the room when the cameras were installed. "I wasn't able to completely conceal myself there, but at least I felt somewhat hidden."

With the cameras in plain view, attached to the corners of the room, her mental state changed as the project progressed, she said.

[Photo courtesy of Plasma Inc.]

[Photo courtesy of Plasma Inc.]

"When I was cooking, my hands would sometimes feel slightly awkward, and I sensed that I was nervous -- but nothing extremely out of the ordinary. But I wasn't quite sure if my behavior changed because of the cameras or because I struggled to devise ways to keep some degree of privacy in this small apartment."

The woman, who has an annual income of 3 million yen, said she only told her closest friends about the experiment. She did not tell her family because they are not in touch, she said. "My one or two close friends are like family to me, so there was no reason to keep it a secret. Their response to me doing it was like, 'Really? Wow!"

The participants were permitted to quit the project at any time. In such cases, they would still be paid for the number of days they had been filmed. They could also request data be deleted.

The woman temporarily stopped one of the cameras in the third week "for about 30 minutes" when she was feeling under the weather. "I just wanted to escape a bit. I didn't want to stop completely, just give myself a little break."

She wasn't particularly concerned about computer passwords or other private information being divulged unintentionally due to the camera angles, either, she said. "It felt like routines you see people doing these days on YouTube, but I didn't have a feeling my private information was being monitored."

She added: "It's not like I don't have any fears that the video content could leak. But I really didn't think about the risks that much. I just thought of this as a 'social experiment.' If I started to be suspicious, there would be no end to it. In that case, I wouldn't have participated in the first place."

Enno, an expert in AI image analysis, envisions creating video archives of the content as a cross-section of consumer behavior to use in fields such as treating lifestyle-based illnesses and developing new medicines in the future. The woman said she is keen to learn how her data content might be used.

She would be open to taking part in the experiment again, as long as the conditions are right. "I think I could even do it for another month, but probably not two months," she said with a smile.

Enno graduated with an engineering degree from Kyoto University in 2014, and while at graduate school there he started the company Rist, which developed a system that used AI to visually inspect products in the manufacturing industry and medical fields. He sold the company to Kyocera Corp. in 2018 before founding Plasma on Nov. 1, 2019.

The Exograph project has received criticism on numerous fronts. For example, there are security concerns about the potential leakage of private information. Others just call the project "creepy."

The company caused a stir in the preliminary stage when it sent out an email that inadvertently revealed many of the applicants' email addresses to others in the group, prompting the company to issue an apology and compensate those affected.

Plasma also was criticized on the internet for exploiting the poor by initially setting the compensation for participants at about 130,000 yen, the same amount people on public assistance receive, before raising the payment to avoid this perception. Some had called it a "poverty business," that is, an activity that might draw many people who are poor and are in desperate need of money.

Where privacy on the internet is concerned, Enno said that people, especially millennials with a strong degree of IT literacy, understand that there is a trade-off for the convenience of using web services such as YouTube and Google for free: you become the target of ads by the companies trading your private data.

"What's interesting about criticism over security concerns is the same thing could be said about the big tech companies who are online. My project is offline and out in the open. But if a person does a search about 'how to commit adultery,' on Google, I think that is even more dangerous because it gives a clear picture of what that person is thinking."

Enno hopes people who participate in future Exograph projects can find a purpose -- a sense of happiness and dignity -- in their real life by contributing their data for others. He suggests there is little resistance to divulging privacy, especially among millennials.

"YouTube is entertainment content. It's a choice, but I think of our project as a private human activity -- the subjects are selling their privacy, but it is still very personal compared to a YouTuber. There is no craving the limelight."

So does Enno think anything is too private to be recorded, whether online or off?

"Personally, I don't think anything is. Of course, this usually means things of a sexual nature, sexual content, or acts. But as animals, we all do it, so there's nothing disgraceful. You can see such images by doing searches on Google or your smartphone...But there should be a choice of whatever a person agrees to show of private life. For people who think their life is too private, they shouldn't participate," he said.

Even so, critics such as Teppei Koguchi, an associate professor in the college of informatics at Shizuoka University, said people participating in the Exograph project should beware of the risks. Even with the identities blotted out by video editing, if their data leaked, the subjects could be determined by their surroundings.

"Even if a subject agrees to the conditions of the project, there is a limit to what an individual has decisions over," Koguchi said. "Their assumptions are not always correct, and sometimes they regret what they've done. Such a business must proceed with the understanding of these limitations."

The ratio of male to female applicants was 4 to 1, and 80 percent of the whole were in their 20s to early 30s with incomes between 2-4 million yen -- closely aligned with Japan's income distribution for this age group. Some applicants earned over 10 million yen per year.

About 60 percent of those who applied to take part were single, and 40 percent were people living together. Nearly 75 percent of the applicants were working people, 7 percent were jobless, and 18 percent were students. Twenty percent of those who applied did so for the money alone, 60 percent for the money and because they found the project intriguing, and the rest, including some sexual minorities and others, to contribute their life data for the benefit of others.

Enno said Plasma has applied for an international patent and already had inquiries from several companies about experimenting on a much larger sample.

Going forward, he plans to consult consumer goods manufacturers, food and beverage companies, advertising agencies, and medical care firms about the commercial applications and specific services that companies might offer people for private video content. He hopes to announce his findings at the end of January.

Enno says for the private data the project generates to be reliable and useful to companies, he would need to scale up to a point at which he filmed at least 10,000 individuals at home.

"The more data are shared, the easier it will be to realize overall optimization in the world. So a model data economy would be one where each individual can each share their private information and be compensated appropriately," Enno said.

By Dave Hueston,

By Dave Hueston,