Life after baseball has already begun for Koji Uehara, and the former major league pitcher is relishing the calm after his abrupt midseason retirement earlier this year and subsequent media tour.

For the first time in 21 years, he is not training in the offseason, and the 44-year-old who dedicated his life to baseball said he is still transitioning from a life of structure to a life of relative normalcy.

(Former major league pitcher Koji Uehara in an interview with Kyodo News in Tokyo on Dec. 16, 2019.)

(Former major league pitcher Koji Uehara in an interview with Kyodo News in Tokyo on Dec. 16, 2019.)

"Every day I ask myself what I'm going to do. Right now I'm seeing all the people I was too busy to see in my playing days and making up for lost time," Uehara told Kyodo News in a recent interview.

"I have no concrete plans for a second career. I'm not that interested in managing a team. I want to build relationships with players, so I guess that's more of a coach's job. I've never had a go-to pitching mentor in my life so I want to be that guy."

Uehara enjoyed a relatively long career, but that does not make it any easier to prepare for life off the field and the inevitable physical deterioration that comes with no longer training like a pro.

It's "weird" how his now-comparatively sedentary life and less-strict eating habits are changing his body, he said. He has not been running or weight training, something he has done every winter since high school.

His identity was built around playing baseball, commuting to stadiums and following throwing programs. But since walking away from all that in May, he has had to live with the fact that the game has gone on without him.

Does he miss it? Of course, he said. But for him, clinging onto hope of returning to his prior glory was not an option. He had the opportunity to go out on his own terms, and he took it.

After starting out the 2019 season on the Yomiuri Giants farm team and going 0-0 with a 4.00 ERA in nine games, he announced his retirement.

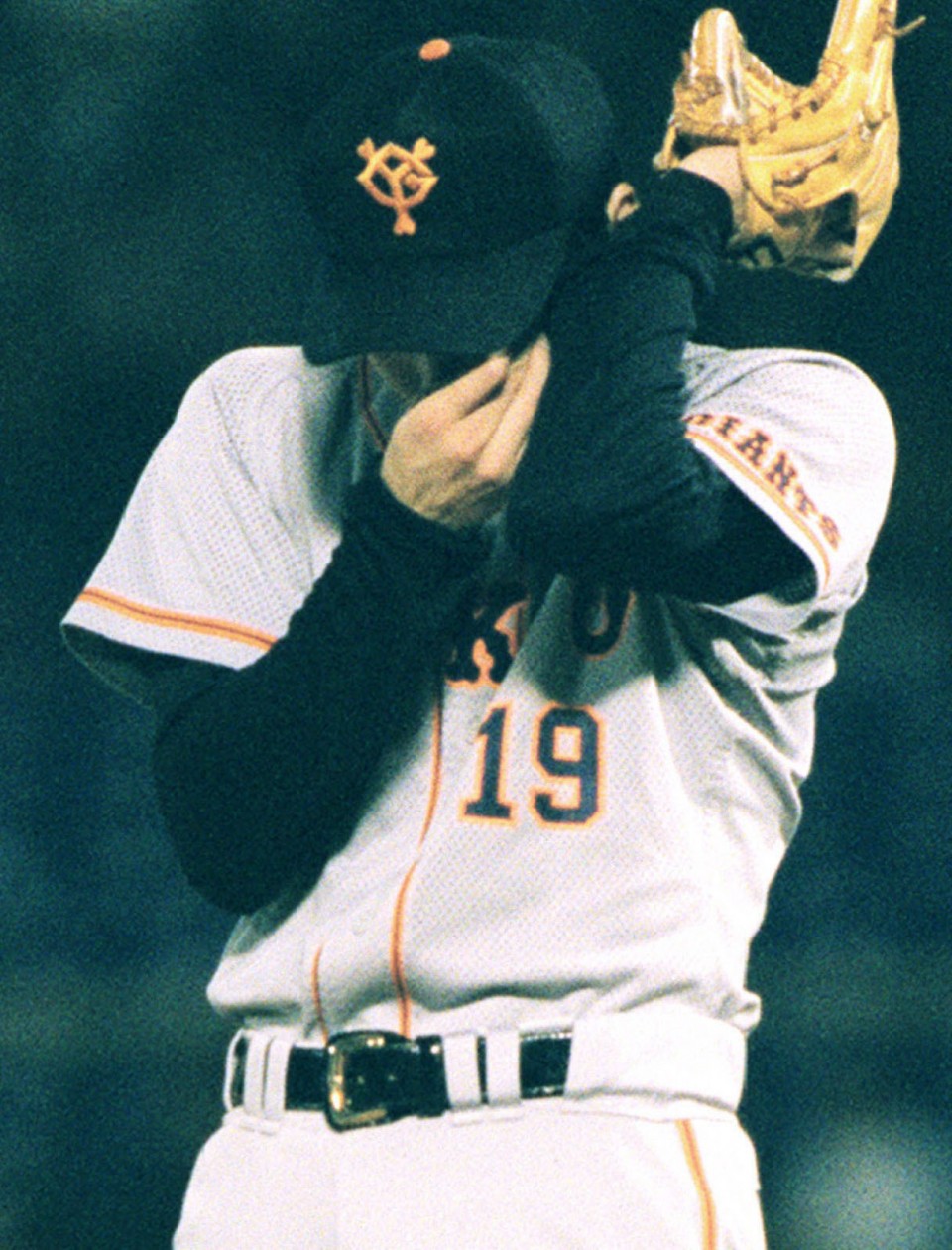

(Yomiuri Giants rookie Koji Uehara cries on the mound after being forced to intentionally walk Yakult Swallows slugger Roberto Petagine on Oct. 5, 1999.)

(Yomiuri Giants rookie Koji Uehara cries on the mound after being forced to intentionally walk Yakult Swallows slugger Roberto Petagine on Oct. 5, 1999.)

"Of course, I would've liked to have waited until the end of the season to announce my retirement, but baseball is a numbers game. I had to let the numbers speak for themselves. It was time I step aside and give younger players a chance," he said.

"I gave myself a three-month deadline but I wasn't getting results or the call-up, so there was no point in delaying retirement. The decision to leave the game is never easy for anyone, but I have no regrets," he said.

Uehara will always be remembered for his antics on the mound, particularly in Japan, a country in which elements of the samurai code of conduct -- self-discipline, self-sacrifice and loyalty to a master -- remain in sports.

In one famous episode in 1999 in Nippon Professional Baseball, Uehara cried on the mound when ordered to intentionally walk a slugger chasing a league home run title. That same year Uehara won 20 games and was named Rookie of the Year.

"I showed disrespect to my manager. That's a cultural no-no. I'm sure I made many Giants fans angry," he said.

Living the life of a professional athlete suited him perfectly, he said, his disdain for losing always being a much stronger emotion than his love of winning meaning he was never short of motivation on the mound.

As someone who has participated in international events as an amateur and in two Olympics, in 2004 and 2008, Uehara knows the Games offer athletes the chance to shine and make their names known.

When asked if he had any advice for the younger, less-experienced players that will make up the national team roster in Tokyo in 2020, Uehara said they should enjoy every bit of the experience -- the attention, the scrutiny, and the spotlight.

"Who knows, it might be the last time we see baseball on the Olympic program. They should feel honored to be on the team and hold onto every moment. They're suspending the (regular) season. It's a big deal if you're one of the 24 players chosen from among the 12 teams."

Uehara was never in it for the money, but he said as an athlete, money, or a team's willingness to pay it, is the clearest measure of "worth."

Though he is not one to dwell on the past, Uehara said he would have gone broke had he taken the minor-league contract the then-Anaheim Angels had offered him in 1998 when he graduated from the Osaka University of Health and Sport Sciences.

"I would've had to spend two years in Double-A and my paycheck was for 100,000 yen (about $900) a month. That's much lower than what developmental players make here. That's a part-time income with full-time effort," he said.

It was a turning point in his career. After rejecting the Angels' minor-league deal, he started his professional baseball career in Japan with Yomiuri and went on to play for the Baltimore Orioles, Texas Rangers, Chicago Cubs and the Boston Red Sox.

He spent 10 seasons with the Tokyo-based Giants, primarily as a starter, but in 436 games in the majors he operated mostly in middle- to late-inning roles.

"I didn't start out as a closer (in Boston), I was a mop-up man, but that season ended magically," he said in reference to 2013, when he got the final three outs in the World Series clincher.

(Boston Red Sox closer Koji Uehara gets lifted by a teammate after the Red Sox defeated the St. Louis Cardinals in Game 6 to win the World Series on Oct. 31, 2013.)

(Boston Red Sox closer Koji Uehara gets lifted by a teammate after the Red Sox defeated the St. Louis Cardinals in Game 6 to win the World Series on Oct. 31, 2013.)

Uehara said his pitching role was never defined in the majors, and it was hard to get used to being a set-up man, where pitchers are never sure when to start their warm-up routine and when to enter the game.

Even after racking up 100 wins, 100 saves and 100 holds between Japan and the U.S., Uehara said he still felt like a Jack of many trades as he was never allowed to master just one, being switched back and forth between relieving and closing in his late years.

He said comparisons between the majors and NPB achieve nothing, but admits to enjoying the respect and freedom he was given by his MLB teams and the tough love he got from the home fans.

And it is an emotion he wants to repay.

Uehara hopes to do what he can to give back to baseball, and will probably find himself connected to the game in some way.

Changing some outdated Japanese baseball traditions is one way he wants to contribute, he said, as the sport's future in his homeland depends on it.

"It's not that one is better than the other. As someone with knowledge of both Japanese baseball and Major League Baseball, I feel like I can offer the best of both worlds to young baseball prospects in Japan," he said.

By Mai Yoshikawa,

By Mai Yoshikawa,