The boy had been coming to play at her home almost daily -- even when her son was not around.

The woman, a housewife in her 30s from the Kanto region of Japan, would treat the child with snacks, and it was not uncommon for him to eat dinner with her and her family, or stay late into the night.

So, when she discovered that he was not a friend of her son, nor even an acquaintance, the woman was dumbstruck as to what the young boy was doing coming to her home so regularly.

(File photo)

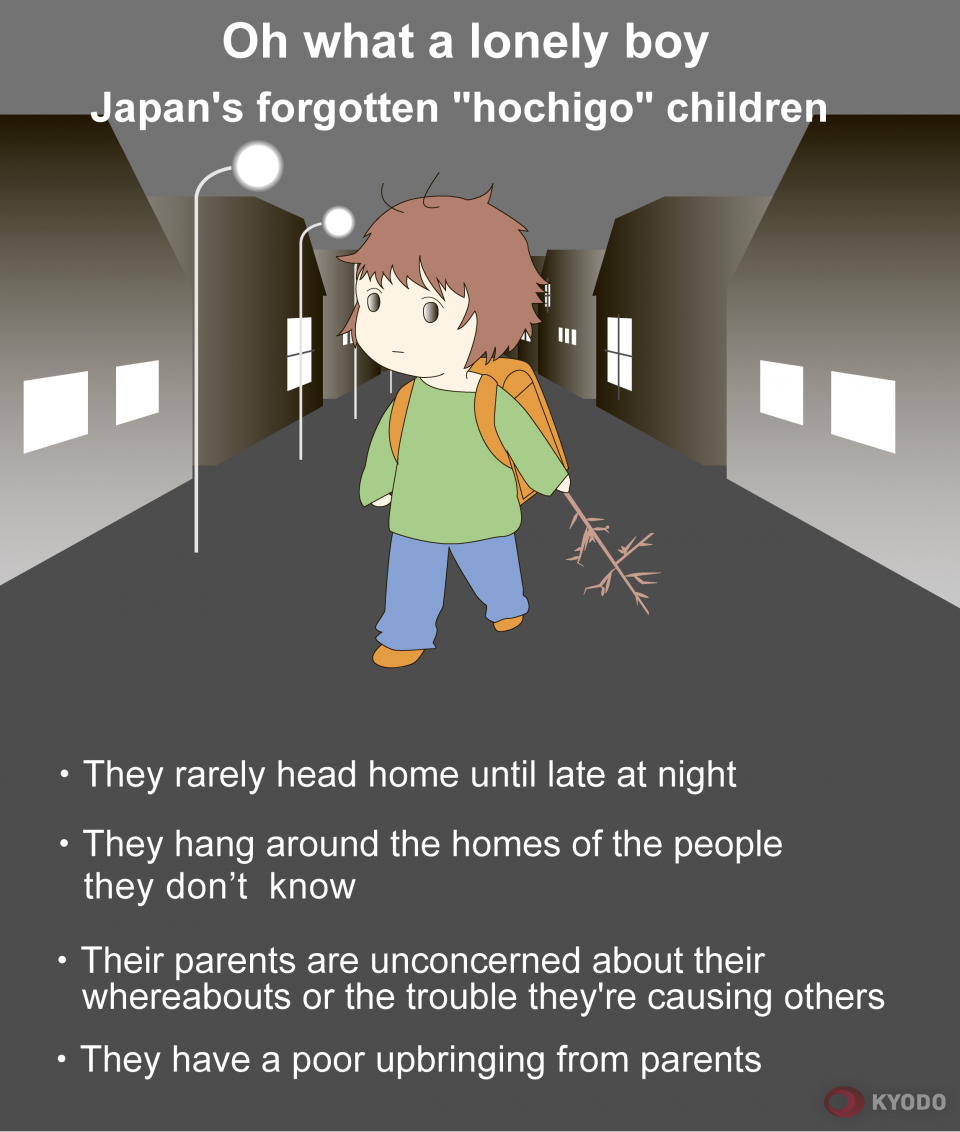

The anecdote, as strange as it is, is being seen in a growing number of places across Japan, with neighborhood children spending time at strangers' and acquaintances' homes, or aimlessly wandering the streets after being left unsupervised by their parents who are absent due to work constraints, or perhaps even simple indifference.

The Japanese word for such children, "hochigo" (literally, left-alone child) even came into the lexicon from around 2010.

Although there are no concrete numbers to determine the extent of the phenomenon, bewildered parents are taking to social media in numbers to vent about the parents who allow their kids to take advantage of their good graces, with some even discussing how to get the kids to leave their homes.

Experts point out that a safety net needs to be built to assist such children and their parents. But the issue is further complicated by the fact that many parents are not aware they are neglecting them in any way, rather thinking they are just allowing them some freedom.

Japan is considered safe, a country where kids are allowed from a very early age to be independent. Neighbors and the wider community foster this autonomy through the general acceptance that children in Japan, much more so than in other countries, are able to look after themselves.

Japanese elementary school children as early as first graders, for example, can be seen walking home from school or riding busy trains alone -- something almost unheard of in other parts of the world.

(File photo)

The earlier-mentioned mother, who asked to remain anonymous, began receiving her mysterious visits when her first-grade son brought a different classmate home after school. Standing behind her son and his friend was another boy who appeared a little older.

But thinking he was also her son's friend, she invited the boy in as well and served them all snacks.

But the boy began coming more frequently and would even take food from the refrigerator without permission, she says. He would hang around, seemingly with no intention of leaving even when it got late. After having her doubts, the woman asked her son about the boy and was astonished when he replied he had no idea who he was.

"In fact, he was a total stranger. My son said he didn't know him at all," she said. After consulting with her son's teacher, the woman found out that the child was a third-grader at the school.

Although the boy stopped visiting her home after she spoke to the teacher, she would often see him hanging around outside, still apparently at a loose end.

Despite Japan remaining a country in which kids can roam, there have been instances in which that autonomy has proven problematic, especially when the internet is involved.

One such recent case saw a 12-year-old Osaka girl allegedly kidnapped and confined by a man whom she came into contact with via social media. He met her and took her on a more than 400-kilometer train journey to his home where he is thought to have held her against her will.

The girl was missing for almost a week before her escape from the man who also was holding another missing girl, identified as a 15-year-old from Ibaraki Prefecture, at his home in Oyama, Tochigi Prefecture. The older girl had been with him for about six months.

A characteristic of parents of hochigo is they have little interest in what their kids are doing after school, experts say. Such parental apathy, they say, can lead to more serious neglect, illness, or in some cases, even life-threatening situations.

A woman in her 40s from Yokohama, near Tokyo, who knows such a child, said, "When the parents both work, it is easy for them to forget about spending time with their children and staying emotionally involved."

"I could see how my own child could easily become like that if I am not careful," said the woman, who also declined to give her name.

According to the education ministry, as of 2018, there were at least 700 groups nationwide setting up seminars for parents to share information on childrearing and promoting awareness about child neglect. Specialists from some of the groups make home visits to consult with those having trouble.

Noa Fukaya, an associate professor at Shoin University who specializes in children's issues, says some parents are uncertain or unaware of the best ways to raise their children, a problem exacerbated in the wake of the so-called post-boom lost decades in which a low birth rate led many to remain childless.

The concern is that because working parents face more pressure, without support from grandparents or extended family in many cases, kids are left alone and become more prone to delinquency, truancy and other problems.

What is obvious is that help must be made available to parents whose kids are being neglected, Fukaya said.

"There is a limit to the support hochigo will get from good-natured individuals. A safety net must be built into society to support such parents and their families."

Related coverage:

Japanese sitting style to be recognized as punishment under new law

Japan early childhood staff feel least valued among 8 nations: OECD

Japan revises law to ban parents from physically punishing children