Due to a wide range of shared values and a desire for regional peace and stability, we support a strong Japan-U.S. alliance.

However, even closer relations are hampered by Japan's continued plutonium production.

Last July, the civilian nuclear agreement between Japan and the United States came to the end of its initial 30-year period of validity and was automatically renewed.

This agreement allows Japan to use nuclear materials and equipment exported from the United States to produce and separate plutonium for peaceful uses.

As of December 2017, Japan had already amassed about 48 tons of separated plutonium, enough to make more than 6,000 nuclear bombs.

This is about equal to U.S. surplus military plutonium.

Japan is the only non-nuclear weapon state which still separates plutonium.

Japan intends to start operating the Rokkasho Reprocessing Plant as soon as fiscal 2021, despite the fact that the government has concluded that reprocessing is not economical.

Once operational, a further eight tons of plutonium can be separated at Rokkasho every year.

(File photo taken in March 2014 shows a spent nuclear fuel reprocessing plant in Rokkasho, Aomori Prefecture, northeastern Japan)

(File photo taken in March 2014 shows a spent nuclear fuel reprocessing plant in Rokkasho, Aomori Prefecture, northeastern Japan)

When its 123 Agreement with the United States was automatically renewed, Japan told the international community it would not "hold plutonium with no use" and would reduce its plutonium stockpile.

But it is clear that the operation of the Rokkasho reprocessing plant and the plutonium reduction policy cannot be reconciled, as only a small number of plutonium-using reactors have been able to restart following the Fukushima accident in March 2011.

Japan's plutonium stockpile and continued pursuit of spent nuclear fuel reprocessing significantly complicates security and nonproliferation challenges in Northeast Asia.

North Korea has long used plutonium separated through reprocessing spent nuclear fuel burnt from a "civilian use" nuclear reactor to make nuclear weapons.

And despite recent, high-level summits to discuss the denuclearization of North Korea, the road ahead remains difficult enough without additional, regional plutonium activities.

North Korea has repeatedly expressed its concern about Japan's large plutonium stockpile, and it could use these concerns during negotiations to suggest it should be permitted to maintain its spent nuclear fuel reprocessing capabilities.

Japan's nuclear reprocessing activities even present challenges for other U.S. allies.

South Korea is pursuing its own nuclear fuel cycle research and development, and many in its nuclear community question why South Korea is not permitted to engage in the same spent nuclear fuel reprocessing activities as Japan despite its equally strong record of adhering to the international nonproliferation regime.

China, a nuclear weapon-possessing state under the Nonproliferation Treaty, the constitution for nonproliferation, is also pursuing efforts to expand its nuclear fuel cycle activities and is in discussions with French nuclear giant Orano (previously Areva) to purchase a spent nuclear fuel reprocessing plant.

Should China's pursuit of large-scale commercial reprocessing become a reality, it too could build large stockpiles of plutonium that could potentially be used for its nuclear weapons program.

Unfortunately, the potential risk of a plutonium avalanche is not exclusive to Asia.

The United States is presently in talks with Saudi Arabia on civil nuclear cooperation. During this dialogue, Saudi Arabia asserted its right to uranium enrichment and spent fuel reprocessing.

Before the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, Iran used to claim repeatedly that limiting "access to peaceful nuclear technology to an exclusive club of technologically advanced states under the pretext of nonproliferation" was wrong and frequently pointed to Japan's nuclear activities as an example.

Now Saudi Arabia refers to Iran and Japan to claim its own "right" to uranium enrichment and spent nuclear fuel reprocessing.

From Asia to the Middle East, the implications of Japan's ongoing nuclear reprocessing activities are far-reaching.

Each additional country that possesses and uses these sensitive nuclear fuel cycle capabilities adds to the risk of new nations becoming nuclear weapons states or producing ever-increasing amounts of deadly nuclear materials that could fall into the wrong hands.

Last year's renewed 123 Agreement between Japan and the United States allows either party to terminate the agreement with six months' notice.

As with the discussions last year between our governments over renewal, we must use this provision of the agreement to turn a serious nonproliferation concern into an opportunity.

Together we can take steps to demonstrate global leadership in limiting the spread of sensitive nuclear technologies and material by, for example, conducting joint research on ways to directly dispose of both commercial and military surplus plutonium and by abandoning the plan to operate the Rokkasho reprocessing plant.

Our failure to act will only increase the nuclear danger to the world and could even spark the next nuclear arms race.

(Seiji Ohsaka)

(Seiji Ohsaka)

[Supplied photo]

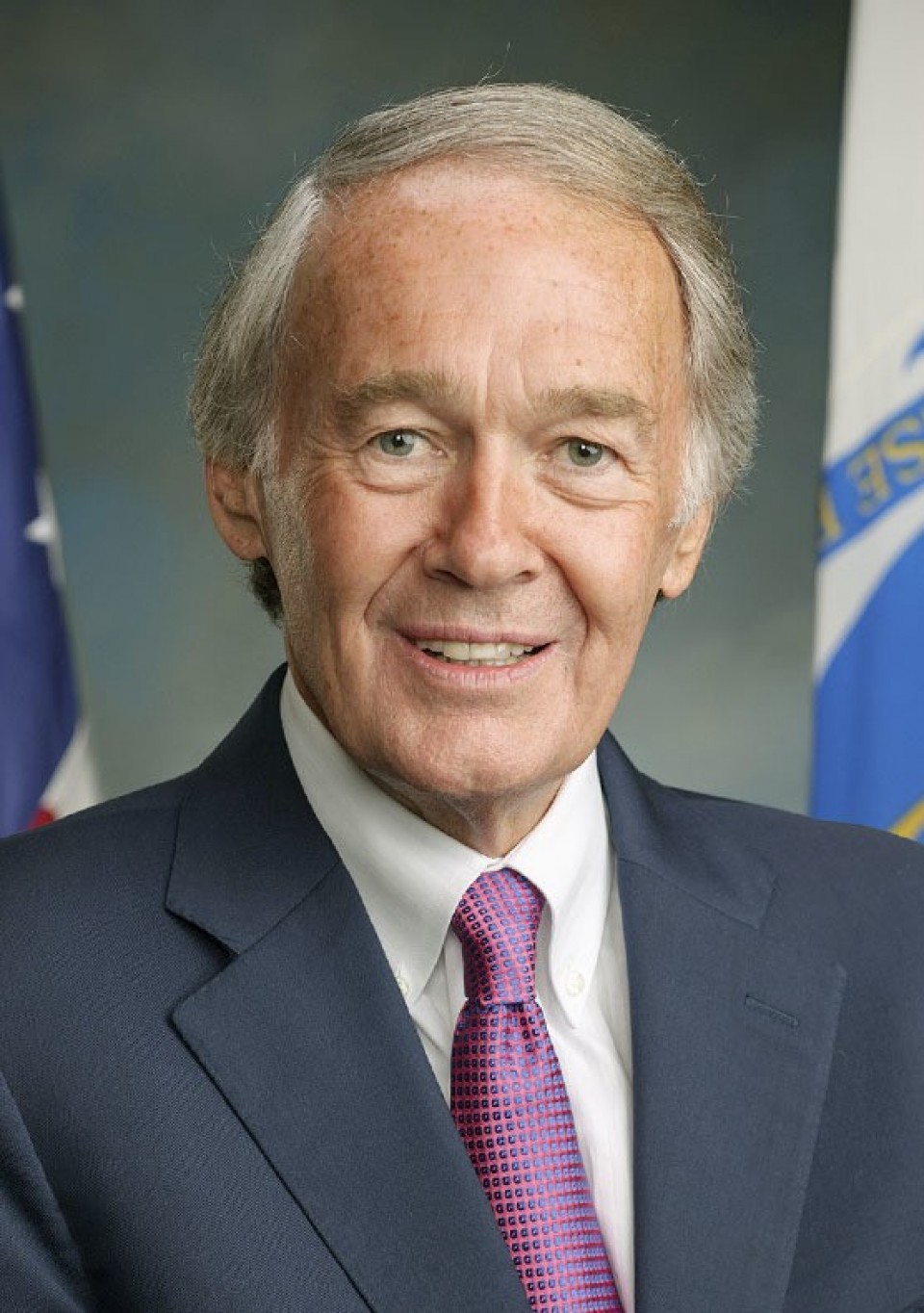

(Seiji Ohsaka is a member of the House of Representatives and Policy Research Council chairman of the Constitutional Democratic Party of Japan. Senator Edward Markey is a U.S. Congressional champion of nuclear nonproliferation. As founder of the Nonproliferation Caucus, he continues to spearhead efforts to prevent the spread of nuclear weapons.)

(Edward Markey)

(Edward Markey)

[Supplied photo]

By Edward Markey and Seiji Ohsaka,

By Edward Markey and Seiji Ohsaka,