Japan has the third largest gross domestic product on earth and has contributed greatly to global stability in a variety of ways.

For years it has been among the largest official development assistance donors on earth. Its outbound capital flows played a key role in ending the Cold War. And Japan was the only nation in the world to raise taxes to help pay for Desert Storm, following Saddam Hussein's invasion of Iraq.

Yet Japan has attracted surprisingly little global attention for its initiatives, however substantive they may have been. Few Japanese leaders have been broadly recognized as pace-setters in world affairs.

Yasuhiro Nakasone developed strong rapport with Ronald Reagan, as Junichiro Koizumi did with George W. Bush. Yasuo Fukuda, Takeo Fukuda, and Masayoshi Ohira were all well-known and respected by Pacific leaders. Taro Aso enunciated ambitious ideas for a Eurasian "arc of freedom and prosperity." Yet the public image of a reactive, even passive Japan has been all too durable on the global stage.

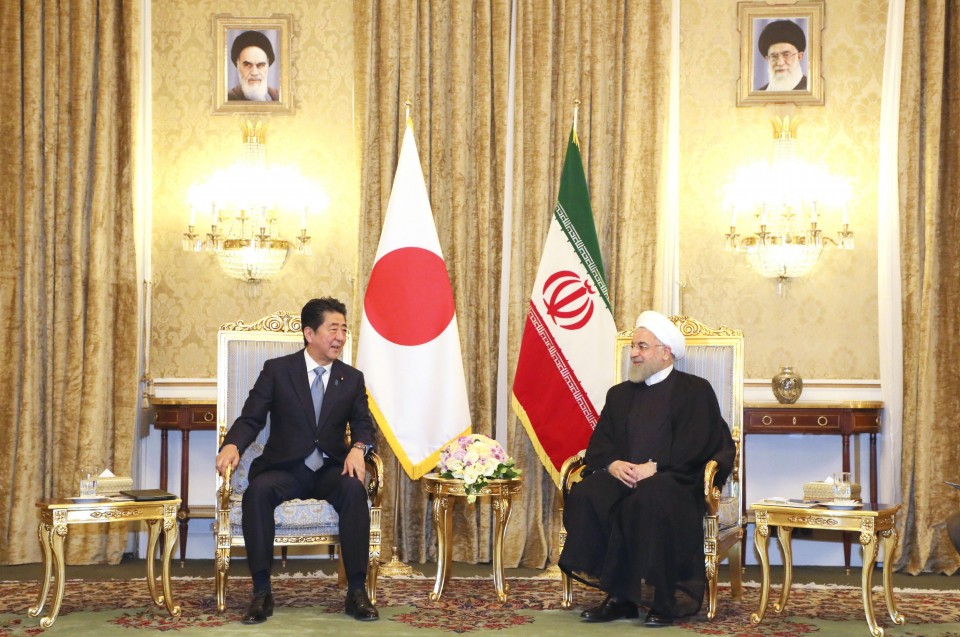

Shinzo Abe has been more visible on the global stage than most of his predecessors, to be sure. In his more than seven years as prime minister -- an extraordinary span, soon to be unprecedented in Japanese history -- Abe has visited around 80 countries.

He has undertaken major bilateral initiatives with India, Russia, and, of course, the United States, cultivating close ties with both Barack Obama and Donald Trump. Yet even those successes have attracted remarkably little attention as global diplomacy.

With the Osaka G-20 meetings now looming, convening countries generating 80 percent of global GDP, Abe at last has a truly global stage. His staff and Japanese ministries have compiled a diverse, thoughtful agenda, on issues ranging from the digital economy to global health.

Yet the centerpiece of the proceedings, transcending these worthy technical questions, could well be curiously unrelated: the dramatic and explosive issue of Iran's nuclear future, and global efforts to cope with that.

The Iran crisis, intensified by U.S. withdrawal from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Acton agreement in May, 2018, and Washington's reinforcement of bilateral sanctions since then, has intensified in recent weeks.

Mysterious bombings in Khuzestan and Baluchistan have been followed by proxy attacks on Saudi tankers and pipelines. Iran has threatened to increase its nuclear output, including reprocessing, if the European Union does not help shield it from U.S. sanctions.

The United States, in response to rising regional tensions, has increased arms sales to allies in the Gulf, while also dispatching bombers, an aircraft carrier, and additional ground forces there.

Among the few major past Japanese initiatives in global diplomacy was Nakasone's effort, on the periphery of the 1983 Williamsburg G-7 summit, to mediate an end to the Iran-Iraq war. Abe now has a parallel, still more substantial, opportunity, on a more consequential stage, in the shadow of the Osaka G-20 summit.

The incentives of the United States, Europe and Iran, as well as even arguably China, are all aligned in favor of a de-escalation of tensions. And Japan, as G-20 chair until this coming December, is strategically placed to mediate that process, on behalf of the broader world.

Iran, Europe and China, for varying reasons, all have clear incentives to stabilize the existing situation, and to blunt the rising tensions of the past several months. All were parties to the original JCPOA agreement, and have traditionally traded extensively with one another.

China, in particular, is Iran's largest trading partner, and has substantially deepened its interdependence with Iran since the 2015 JCPOA agreement. Yet China too has much deeper relations with the United States than with Iran, the current U.S.-China trade war notwithstanding. Beijing does not want its trans-Pacific relationships complicated even further by tensions in the Persian Gulf.

The key question mark, of course, is America under the Trump administration, which repudiated the Obama-era JCPOA agreement, and seeks further concessions from the Iranians.

[Photo courtesy of the Iranian Supreme Leader Press Office]

[Photo courtesy of the Iranian Supreme Leader Press Office]

For the past two years and more, the United States has been escalating pressures against Tehran, with many viewing that escalation as an effort at regime change, analogous to Reagan's successful pressure on the Soviet Union, leading to its ultimate collapse.

Trump, in particular, now seems to prefer a new approach, noting explicitly in recent days that the United States seeks only to prevent Iranian acquisition of nuclear weapons, and not regime change.

To understand Trump's seeming change of position, the best analogy, of course, could be North Korea. Trump sharply escalated military pressure on Pyongyang during his first 18 months in office, and then agreed to meet with Kim Jong Un personally in Singapore.

Even Jimmy Carter, otherwise a sharp Trump critic, applauded the Singapore summit with Kim, commenting that if Trump succeeded at a peace agreement with the North he would be a worthy candidate for the Nobel Peace Prize.

With the 2020 U.S. Presidential election looming, and frustrated on other fronts, Trump could be looking for a repeat in the Middle East to his dramatic overtures in Northeast Asia, and interested in enlisting Prime Minister Abe's help in achieving it.

Three constraints on a direct U.S. overture to Tehran clearly exist. They are Israel, Saudi Arabia (also a G-20 member, and the next G-20 chair), and American domestic politics.

With Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu struggling amidst a difficult re-election campaign, Israel cannot actively complicate dialogues with its arch-enemy Iran at the moment.

The Trump administration seems unlikely to make any significant concessions to Tehran, but President Trump may well be interested in a dialogue, at least indirectly. To neutralize Saudi and U.S. domestic resistance, it is clearly easier for Trump to have Japan mediate with Iran than to deal with Tehran itself.

Japan is thus now on center stage, as the Osaka summit prepares to open -- not only on the technical questions of G-20, but on major global issues of war and peace as well.

(Kent E. Calder is director of the Reischauer Center for East Asian Studies at SAIS/Johns Hopkins University in Washington.)

Related coverage:

Abe urges Rouhani to avoid escalation of Iran-U.S. tensions

Iran spurns Japan's efforts for mediation with U.S.

Abe's mission not yet accomplished as U.S.-Iran hurdles remain high

By Kent E. Calder,

By Kent E. Calder,