A scandal at a medical university in Tokyo, which for years deducted points from the entrance exams of female applicants, has led many aspiring female doctors to utter "I knew it."

"I have heard that many medical universities (in Japan) manipulate the scores in entrance exams to give higher scores to men," said an 18-year-old girl who goes to a prep school in the capital for medical universities. She was speaking after Tokyo Medical University admitted Tuesday it had blatantly discriminated against female applicants for years.

Related coverage:

Tokyo med univ. admits curbing women's enrollment, vows to stop

A report into the university's enrollment policy released that day by a group of lawyers said the medical school did so because female physicians, "as they get older, engage in decreased activities as doctors."

Knowledgeable sources have said that the university set a female student intake ceiling of about 30 percent, and did so as it believed producing a higher percentage of female doctors would lead to a doctor shortage at affiliated hospitals because female doctors tend to resign or take long periods of leave after giving birth.

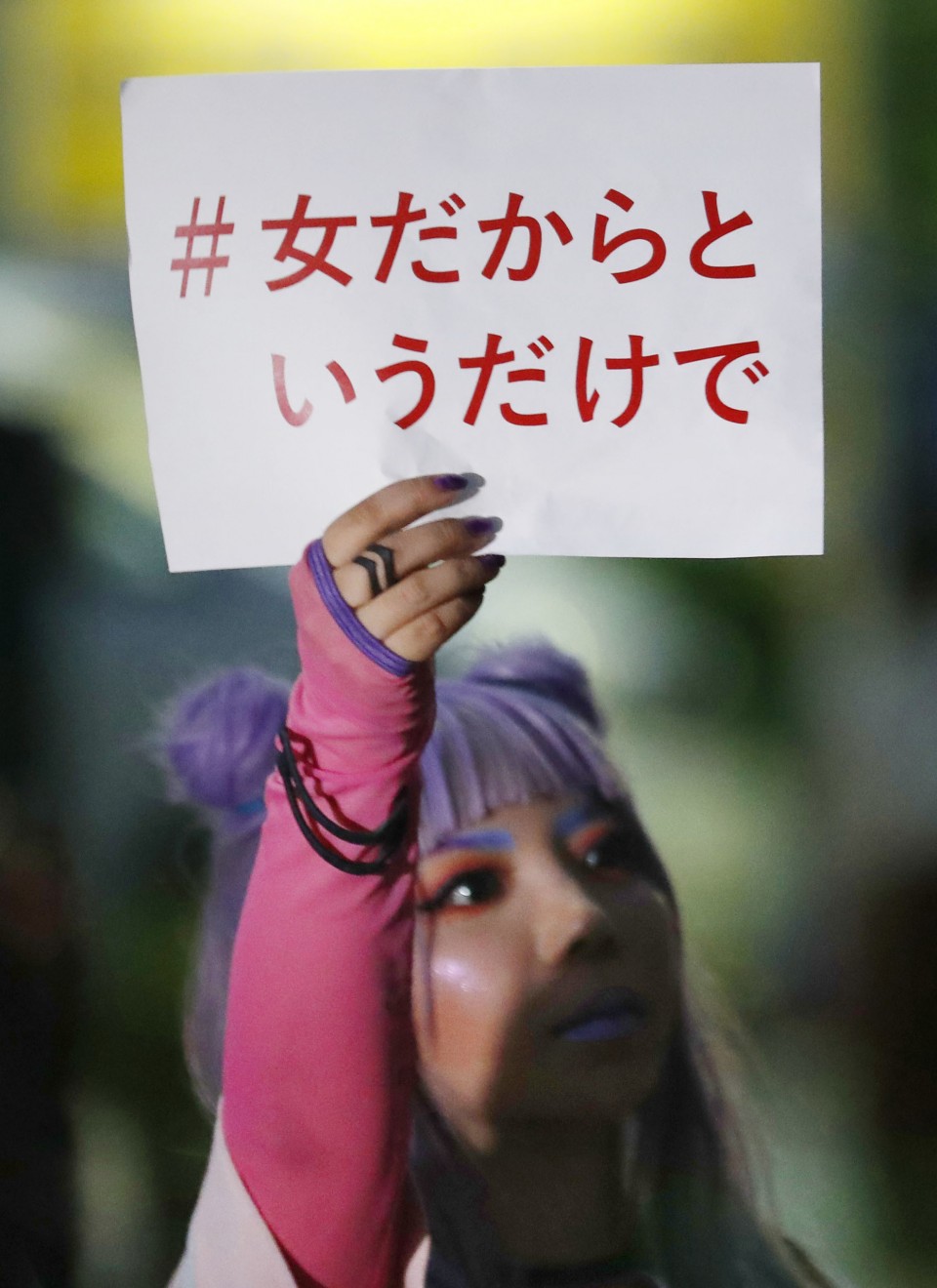

(A protester holds up a sign saying "Just because we are women")

(A protester holds up a sign saying "Just because we are women")

A man in his 50s, who has taught at a prestigious prep school for medical universities in Tokyo for 25 years, said he advised female students to be aware of the cold shoulder women face from medical schools.

"I tell them that in the first place, they have to study on the basis that women are at a disadvantage in applying for medical school," he said.

Government statistics show that the proportion of female students in medical schools increased sharply from 18.8 percent in fiscal 1987 to 30.0 percent in fiscal 1997.

Yet since then, the percentage has risen little -- to 32.6 percent in fiscal 2007, and to 33.3 percent in fiscal 2018.

This year women accounted for 34 percent of the 9,024 people who passed the national certification exam to become a doctor.

The biggest obstacle to increasing the percentage of women admitted to medical school seems to be the strong belief that remains in Japan that women should primarily raise children and do household chores.

That gender role, combined with Japan's long working hours, particularly for doctors, make it extremely difficult for female doctors to continue working after becoming mothers.

The 35-year-old husband of a doctor said his wife is mainly in charge of childcare despite her long work hours because society believes "men don't need to help around the house."

In a reflection of the severe working environment for female physicians, an online survey earlier this month to which 103 doctors responded showed that 65 percent said they "can understand" or "can understand to a certain degree" Tokyo Medical University deducting points from the entrance exams of female applicants.

Many said such treatment "can't be helped" because male doctors have to bear extra burdens when female physicians cannot work due to pregnancy, childbirth and childcare, according to the survey conducted by M. Stage Co., which publishes an online magazine for female doctors.

A female doctor in her 40s talked with Kyodo News about her mixed feelings toward that issue.

The woman, who worked full-time as an internal medicine specialist at a public hospital in Tokyo until this spring, said she cannot tolerate the discrimination against women in enrollment because "women are absolutely better than men in exams."

"But at the same time, I doubt if it's really a good thing to increase female doctors, say, to a degree of 80 percent of the total."

As of the end of 2016, women accounted for 21.1 percent of all doctors in Japan. About 85 percent work as either dermatologists or ophthalmologists because those specialties lend themselves better to set, fixed office hours, while only 5.8 percent of female physicians worked as surgeons.

"We need more surgeons and doctors who can respond to emergencies," but having more woman doctors would exacerbate that problem, said one doctor speaking on the condition of anonymity.

The scandal at Tokyo Medical University surfaced as the Japanese government is striving -- to use the words of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe -- to create "a society where every woman can shine."

In 2017, the World Economic Forum ranked Japan 114th out of 144 countries in terms of gender equality.

Some doctors, both women and men, said the scandal should serve as a catalyst for changing the working environment of physicians.

"Women can work properly if hospitals implement proper work systems such as doctors working shifts and several doctors being assigned for one patient," said a 39-year-old obstetrician and mother of two.

And ultimately the sorts of changes needed may affect Japanese society as a whole.

"The university's scandal is not just about entrance exams but poses a question of how a man should work," said the female doctor's husband who doesn't help around the house. But he said he intends to change the habit of staying at the office until his boss goes home.