On the morning of Aug. 6, 1945, 13-year-old Setsuko Nakamura was on the second floor of a wooden building in Hiroshima with her classmates when a blue flash of light engulfed her.

"I floated in space and lost my senses," she said, recalling the U.S. atomic bombing of the western Japan city. When she regained consciousness, she found herself trapped under rubble. All was silent except for the moans of her classmates.

A soldier found her. "Don't give up. See the light? Crawl towards it," she was told. She survived, although she lost several close relatives and friends in the attack.

The girl grew up to be a famed peace advocate, who now lives in Toronto as Setsuko Thurlow following her marriage to a Canadian man.

A campaigner for the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons, or ICAN, she gave a speech on its behalf at the award ceremony when it won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2017 for its efforts leading to the adoption of a U.N. treaty outlawing nuclear weapons.

Thurlow, whose autobiography, "Crawl Towards the Light," was released earlier this year, has been in Japan since October to give speeches in Tokyo and her hometown Hiroshima.

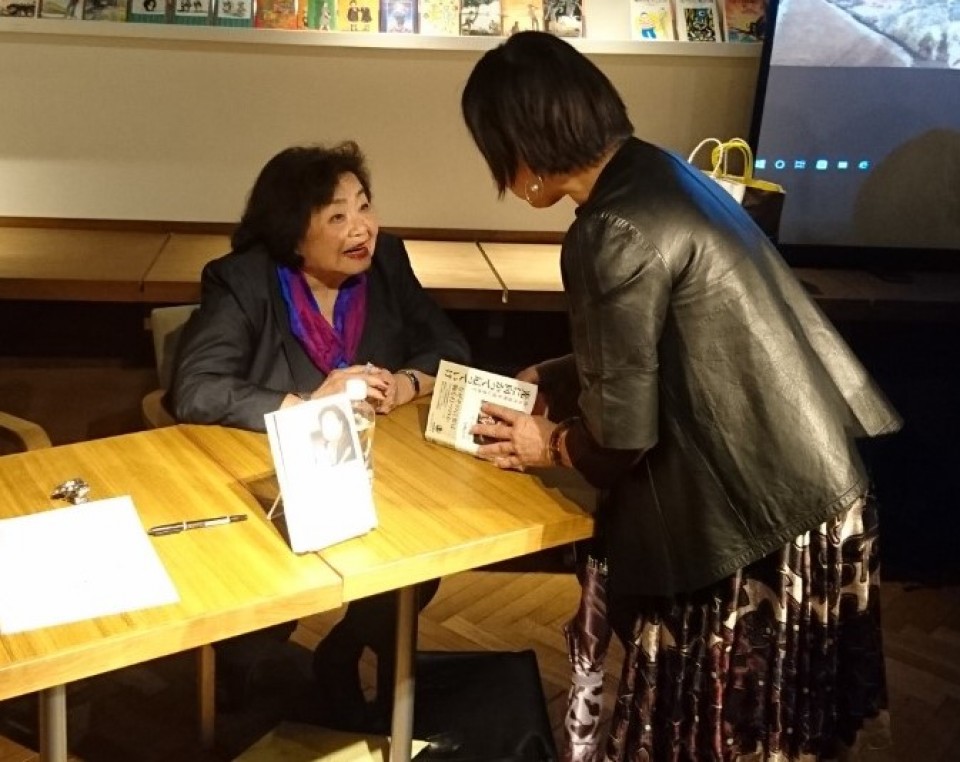

(Setsuko Thurlow (L) speaks with an attendee at her lecture session in Tokyo)

(Setsuko Thurlow (L) speaks with an attendee at her lecture session in Tokyo)

"It was just like our humanity was rejected when the atomic bomb was dropped on us," the 87-year-old told an audience of some 100 people in Tokyo. "I have to say we should not rely only on atomic-bomb survivors if we cannot tolerate the reoccurrence of such an inhumane act. It is the responsibility of all of us."

Referring to her high school and college days in the postwar period in Hiroshima, Thurlow said, "I, as a teenager, could see people working hard to create a society of peace and freedom. In that sense, I was really privileged."

It was through voluntary work at this time that she met her future husband, who was a missionary and English teacher.

After graduating from Hiroshima Jogakuin University, Thurlow started research on social welfare at a university in Virginia in the United States, and the move brought home to her how different attitudes were among Americans at the time about the nuclear attacks.

She recalled the criticism she faced for remarks she made in a newspaper interview about the 1954 U.S. hydrogen bomb test in the Pacific Ocean, in which the Japanese tuna fishing vessel Fukuryu Maru No. 5 suffered radiation poisoning.

She told a reporter that Hiroshima and Nagasaki should have constituted the end of nuclear tests, not their start, denouncing the U.S. policy of building up its nuclear capabilities.

The comment drew harsh rebukes, such as "Don't forget Pearl Harbor," and "Go back to Japan if you don't like the United States."

"I was at a loss as to how I should behave, and I felt lonely," she told the Tokyo audience. "But I eventually determined that I am obliged to tell the creator (the United States) of the atomic bombs what nuclear weapons would bring about. The sense of responsibility enabled me to dispel my loneliness."

After starting a family in Canada with her husband, with whom she has two sons, Thurlow worked as a social worker, occasionally sharing her experiences as a hibakusha at the request of teachers and others.

She also organized an exhibition in Toronto in 1975, the 30th anniversary of the atomic bombings, to give her account of the Hiroshima attack, in cooperation with the Hiroshima municipal government and the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum.

"In Canada, nothing was reported on atomic bombings even on Aug. 6," she said. "I felt it necessary to break this silence."

Her anti-nuclear activities have gradually expanded since then to speaking out at the United Nations about the tragedy of Hiroshima and urging governments to ratify the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. She said its adoption was "like a dream come true following my 70-year struggle as a hibakusha."

Nuclear states such as the United States, Britain, China, France and Russia have declined to endorse the treaty, as have nations under the U.S. nuclear umbrella such as Japan and South Korea and NATO members.

Touching upon Japan's stance toward the treaty, Thurlow told the Tokyo audience, "The government says Japan is the only country to have suffered nuclear attacks, but it always dodges back under the U.S. wing when it makes important decisions."

"I feel quite upset as we, hibakusha, have been betrayed by our government and have been left behind...The government has not listened to our voices even 74 years after the atomic bombings."

Akira Kawasaki, an ICAN international steering committee member, said Thurlow is a powerful voice for nuclear disarmament. "She is a plain speaker and makes no attempt to conceal her anger."

"Hibakusha, like Ms. Thurlow, have a great impact when they talk about the nuclear issue," he said. "While their average age is over 82 years old, I expect their voices to lead to" the total abolition of nuclear weapons.

Thurlow is now waiting for the visit to Japan by Pope Francis later this month, following her meeting with him at the Vatican in March.

Elected as pontiff in 2013, the pope has called for the abolition of nuclear weapons, and the Holy See was quick to ratify the treaty outlawing them. During his stay in Japan from Nov. 23 to 26, he is scheduled to visit the two atomic-bombed cities.

During an interview with Kyodo News in Tokyo, Thurlow said she had presented him with a landmark work by U.S. journalist John Hersey on the Hiroshima bombing. Entitled "Hiroshima," the work is an account on six atomic-bomb survivors.

Meeting the pope in a wheelchair, she recalls "the pope was huddled in front of me and shook my hands."

"I expect that the pope will urge the Japanese government as well as the public to join the effort to make the treaty take effect."

The number of states that have ratified the pact has exceeded 30, although this is still short of the required 50 for the treaty to become effective.

The autobiography is co-authored by Yumi Kanazaki, a reporter at the Hiroshima-based Chugoku Shimbun who interviewed Thurlow for the daily's serial articles last year.

"Ms. Thurlow has remained vocal about the inhumanity of the atomic bombings even in the United States and Canada, and we have been encouraged by her," Kanazaki said. "I wanted to report about her long journey and show respect for her struggles at home and abroad."

By Keiji Hirano,

By Keiji Hirano,