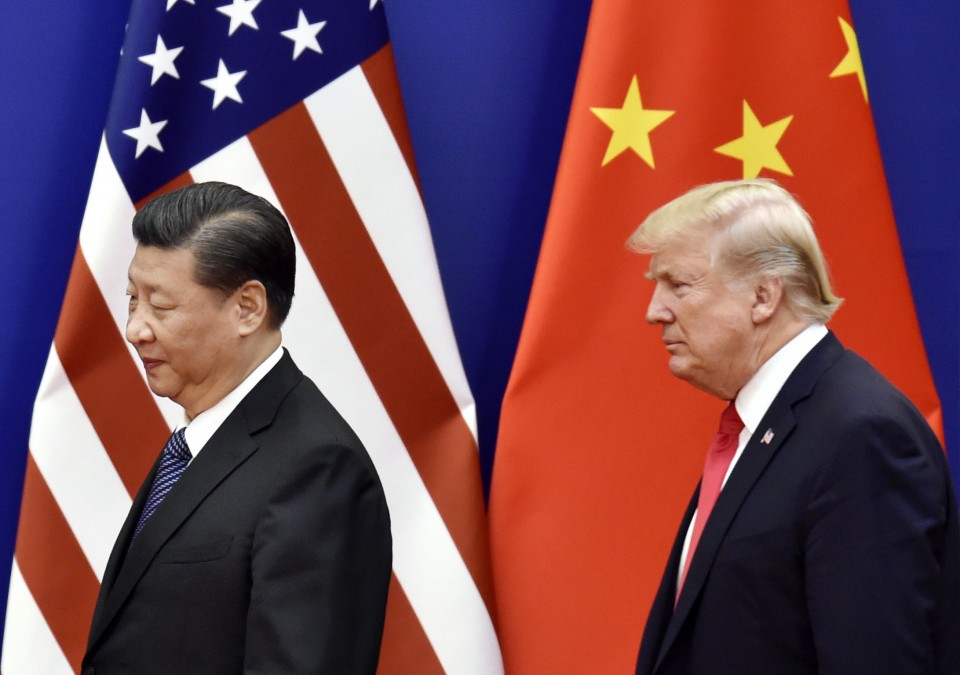

China's economy, which has posted its lowest quarterly economic growth in nearly 30 years against a backdrop of trade spats with the United States, is likely to be plagued by another headache -- Hong Kong.

As the Hong Kong economy has been facing the risk of a recession with months-long pro-democracy protests escalating, the city could lose its status as an international financial hub, possibly eroding direct investment to China, analysts say.

Moreover, recent U.S. moves to revoke the special economic privileges that Hong Kong has enjoyed would also decelerate growth of the mainland, which has been heavily dependent on trade through Hong Kong, they added.

If the economic draw of Hong Kong is diminished, many foreign firms may become reluctant to operate there, "dealing a further blow" to China's economy, said Naoto Takeshige, a researcher at the Ricoh Institute of Sustainability and Business in Tokyo.

During the July-September period, China's economy grew at its slowest pace since 1992 when quarterly gross domestic product data became available, expanding 6.0 percent from a year earlier, according to Friday's data, which excluded Taiwan, Macau and Hong Kong.

Most notably, China's trade with the United States, one of the major drivers of economic growth, plunged 14.8 percent from the previous year for the nine months from January, blurring the outlook for the world's second-biggest economy.

Over the past four months, meanwhile, there have been protests almost every weekend in Hong Kong, many turning violent. The unrest was initially triggered by a now-abandoned extradition bill that would have allowed citizens there to be sent to mainland China for trial.

"The Hong Kong economy has taken a big hit since the protests started in June," said Paul Luk, an assistant professor in the department of economics at Hong Kong Baptist University.

"In August, retail sales fell by around 25 percent and tourist arrivals by almost 40 percent year on year," he said. "Going forward, we are expected to see more negative figures."

A leading indicator of economic policy uncertainty for Hong Kong has "remained at an elevated level over the last three months, which is suggestive of more cutbacks in business investment and domestic consumption in the months to come," Luk said.

Victor Teo of the University of Hong Kong said an economic downturn in one of the special administrative regions of China would not adversely affect the mainland's economy "significantly," given the size of the city's economy.

"Around two decades ago, Hong Kong's economy accounted for one-fourth of China's GDP," but is now only "about 3 percent," he said.

Other observers, however, point out that if the economic circumstances in Hong Kong deteriorate further, mainland China would be deprived of ways to earn money from abroad and the nation's business activities have become more lackluster.

Under the framework of "one country, two systems," Hong Kong was promised it would enjoy the rights and freedom of a semi-autonomous region following the former British colony's return to Chinese rule in 1997.

The city has since then developed as an international financial hub, while China -- whose capital market has yet to be entirely liberalized under socialism -- has kept Hong Kong as an open channel to connect with the world.

(Hundreds of people march in Hong Kong on Oct. 12, 2019 protesting against an emergency ban on wearing facemasks during public assembly.)

(Hundreds of people march in Hong Kong on Oct. 12, 2019 protesting against an emergency ban on wearing facemasks during public assembly.)

"U.S. and European companies have carried out direct investment in mainland China through Hong Kong," said Naoki Umehara, a senior economist at the Institute for International Monetary Affairs in Tokyo.

Unless Beijing completely lifts financial regulations, Hong Kong "will not be easily replaced by other cities" in China, he added.

Currently, more than 60 percent of China's foreign direct investment has been channeled through Hong Kong and about 70 percent of its capital has been raised on the stock exchange in the city, the Hong Kong Trade Development Council said.

Another development that could weigh on the Chinese economy is a potential enactment by the United States of a human rights bill aimed at supporting anti-mainland protests in Hong Kong.

If passed, the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act would require the U.S. secretary of state to regularly certify whether Hong Kong is sufficiently autonomous to justify special treatment by the United States for bilateral agreements and programs.

A 1992 U.S. law gives Hong Kong a special status separate from the rest of mainland China with regard to tariffs and visa restrictions.

But should the U.S. administration judge that Beijing-backed Hong Kong authorities do not respect human rights, such special treatment would end, in turn dragging down China's economy with the city becoming less attractive as an investment destination, pundits say.

The United States is certain to continue "trying to put China off balance over human rights issues," said Takahide Kiuchi, an economist at Nomura Research Institute, indicating that the Chinese economy will remain in a difficult situation for the time being.

Related coverage:

Huawei CEO voices strong hope for cooperation with Japan amid U.S. fight

Hong Kong police say 201 arrested in latest protests

By Tomoyuki Tachikawa,

By Tomoyuki Tachikawa,